MORE CHRONICLES FROM EXMOUTH JUNCTIONINTRODUCTION Earlier I introduced you to an insight of the Southern Region’s operation in the Exeter area of the West of England, previously this mainly examined the working of the scenic Seaton branch and described the requirement to lodge away in these times, plus pick-up goods and stone train workings. Well there’s more, and I’m pleased to now present the second series of ‘Chronicles from Exmouth Junction’ written thirty-five years ago by my old friend Ted (‘Smokey’) Crawforth. This time detailing the duties worked at Exmouth Junction depot (72A). Duties that the footplate crews in the numerous links were booked that covered the various lines in the counties of Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. This series covers his initial arrival at the depot and the progress that he made through these links. Equally it details the interesting locomotives that made up the depot’s allocation of locomotives that were then booked to work trains over many of these lines, some that sadly exist no more. Whatever take the opportunity and enjoy these memories that have been recorded for posterity, lest we forget!

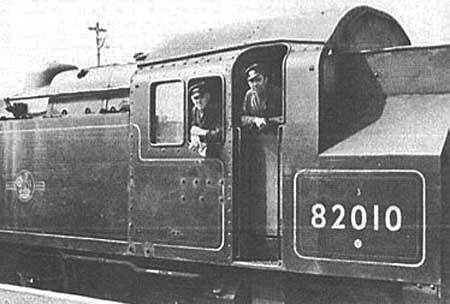

Many of you reading this will recall the period at Nine Elms when the GWR Class ‘57xx’ 0-6-0PT came to the depot to replace our ageing former LSWR ‘M7’ and LBSCR ‘E4’ tank engines. They were not popular is an understatement and when they finally left their replacements were much more readily accepted. The ‘BR Standard 3’ 2-6-2T tank engines were well suited to the work they then performed at Nine Elms. Sadly they were the very engines that were employed on the Exmouth and Sidmouth branches that had been taken over, due to regional changes, by the Western Region. Steam operation abruptly ended and these locomotives were moved on. In fact I recall bringing one of them ‘light engine’ from Salisbury to Nine Elms in 1963. Checking my records I worked on the following; 82010, 82011, 82012, 82013, 82014, 82015, 82016, 82017, 82018, 82019, 82022, 82023, 82024 & 82025, all splendid little engines! Jim Lester – 70A

ARRIVALS AND DEPARTURESWritten by Ted ‘Smokey’ Crawforth and reproduced with the help of Jim Lester Someone suggested that some accounts of my time on the footplate in the Southern territory west of Salisbury might make interesting reading. In coming to write my reminiscences I came to to the conclusion that what I wanted to put across was not that locomen are a cut above the rest or more important, but because of the nature of the job with our variable hours of work and the constant movement from place to place, they are different. The locomotive always seems to get the lion’s share of the enthusiast’s attention being the driving force of the railway and inevitably the men working with motive power inherit some of the glamour. Certainly the glamour associated with that most individual of creations, the steam locomotive, rubbed off on locomen. Back in May 1959 when based at Norwood Junction shed I received a letter from the shedmaster, Mr Standon, that told me that my application on Vacancy List No 25 of 1954 had at last been successful. I was duly appointed fireman at Exmouth Junction shed as from 15 June. It had taken so long because promotion was very slow at that shed, in contrast to Norwood Junction which had probably the quickest promotion rate on the Southern. On 14 June I packed my bags and caught the 23.19 pm Wallington to Wimbledon, then into Waterloo where before long I had settled down in the stock of the famous 01.10 am newspaper train to Exeter, made up of seven coaches and ten vans. Things were running a little late the newspaper world and hauled by rebuilt ‘Battle of Britain' pacific No 34062 then at 01.10 left 7.1/2 minutes late but arrived in Exeter Central on the dot at 5 o’clock. What was there to do at Exeter Central at 5 o'clock in the morning? I went to the waiting room and got my head down for a couple of hours. Then, as I was not expected at the depot until 09.00, I set off to see my future landlady, having previously arranged lodgings through the help of a friend. Sharp at nine I reported to Exmouth Junction shed, a little over a mile east of Exeter Central on the main line, where the Exmouth branch diverges southwards. I first saw the running foreman (who was called Jack and smoked a pipe), told him who and what I was and went on to the office of Mr Moore, the newly appointed shedmaster. His room was so spick and span that I took my hat off and all but stood to attention in front of his table. 'Ah, so you're the fireman from Norwood. Have you done any work over this side before’? ‘No sir. I've been mainly on the Brighton line – the Central section’. We had a little chat about the job the different classes of work at Exmouth Junction and of course the types of engines working there at that time: ‘02’, ‘M7’, ‘T9’, ‘700’, ‘Z’, ‘N’ and BR 3 Standard tanks as well as engines bigger than I had encountered at Norwood - the 'West Countries' (original and rebuilt) and ‘Merchant Navy’ class, now all rebuilt except No 35006 at Salisbury shed and 35028, then at Stewarts Lane. I saw some of the old original Brighton ‘E1/R' 0-6-2Ts in the shed, but they disappeared by the end of the year and I did not get another chance of working on a Brighton engine. The shedmaster then said: ‘Of course, you'll be wanting to spend the rest of the day looking for lodgings’? ‘Well I've already got my lodgings ....! 'You'll be wanting to spend the rest of the day looking for lodgings’? '’Yes sir, but I've already got lodgings. ‘You'll be spending….’ ‘Yes sir, I'll be spending the day looking for lodgings’! So the interview ended with him shaking my hand and saying. ‘I hope you'll enjoy yourself here and keep out of trouble', and that I was to be back at 8 o'clock the next morning. On Day 2 the New Boy from Norwood reported again to Jack for a look round the shed. I began to realise what I'd let myself in for: from the five road shed at Norwood to this — a twelve road shed, with a lifting road, a spare road out behind the shed wall and other nooks and crannies I hadn't realised were there. The lifting road was the first one inside the shed and with its high roof to accommodate the crane which could lift anything up to a ’Merchant Navy’ it reminded me of a cathedral. It was not unusual to come in and see a Pacific poised for 'lift off with one end on packing and the other under the crane, and. perhaps, a pair of driving wheels out. I also had to get used to an allocation of over 100 engines, and some 200 crews: indeed, there were more than 400 staff on the depot, including labourers, gland packers, fitters, coalmen, ashmen, cleaners, firemen, drivers, storemen, clerks and timekeepers, and any I have missed out. You never saw that many because they were spread over the shifts and only 20-30 men were around at once. This shows, of course, that the railway was an important employer in a city like Exeter. At Exmouth Junction, the work, too, was different, with longer runs than I had been used to previously. There was lodging away work which we had never thought about at Norwood and in due course I went on lodging turns to Seaton. Lyme Regis and Bude and was on loan to Okehampton, Yeovil and once to Barnstaple.

After the first look round, Jack introduced me to my duties. He sent me out with a ‘Merchant Navy’ ‘prep’ fireman: these were men just graduating from passed cleaner and were virtually their own bosses as they went round filling sandboxes, trimming coal, and generally assisting the rostered fireman on preparation and disposal work. This was done because these pacifies were considered to be that much bigger than all else and required more time for shed duties. Incidentally I believe that on the London Midland Region the ‘Duchesses’ and ‘Princess Royals' were similarly attended to by spare drivers men who had come off the road through ill health or for other causes. So I started off at the deep end, the first job being to assist getting MN No. 35009 ready for No 526 duty: off shed at 10.07 for the 10.30 up Waterloo. This was my first professional encounter with a Bulleid Pacific, and it was made memorable by nipping my fingers in those peculiar sliding cab windows. After we'd finished her we had a cup of tea and then had to dispose of two engines: 'West Country' No. 34034, in off the North Devon line and ‘Battle of Britain' No. 34052 up from Plymouth. Soon it was ‘cup of tea’ time again, and to finish off we did the sands on original Bulleids No’s. 34011 and 34060. The men didn't use the numbers written here: Pacifies were ‘Thirty four eleven', etc. while for older types we dropped the first '3' so that an ‘S15’ would be 'Eight forty four', an ‘N’ Eightcen-thirty’ and so on. I booked on at 8 o'clock all that first week as a spare fireman. The next day I was with Les Lodge, one of the Lodge brothers, famous in the 'racing pages’ of the railway magazines but by then not far from the end of his career. The first job was to prepare ‘S15’ No 30844, which meant to check tools and sandboxes, make sure the smoke-box was all right and fill and trim the lamps. Then we were back to the disposal road to square up ‘MN' No. 35007 and ‘N15’ No 30451 the latter in off of a down stone train with Yeovil depot men. The second week I was out in the yard at Plymouth Junction, getting tangled up in the shunting. We had ‘Z’ 0-8-0T, the only home grown Southern eight coupled design and made up from various bits and pieces. The main item was a ‘C2X’ class boiler, which as a Brighton design was a good steamer, but the three cylinders were too much for it and steam could not be maintained over long periods, although the boiler was all right for the short bursts of effort which you got in shunting. The ‘Z’s were good shunting engines, we called them ‘Ducks’ from the way they waddled off up the yard with their strings of wagons. The yard worked round the clock, the engine coming in for servicing around 23.00 and going out or being replaced by a fresh one at 03.40.

I was on at 12.45 to relieve at 13.00. We had No. 30956 that week and No.30954 the next. This fortnight could be looked on as a training period, although it was probably not officially designated that way at the time - and it was certainly a period in which to get used to things. You can get used to things pretty quickly when you have to. such as that although the basic signals for shunting were the same as elsewhere, they were applied differently. I was accustomed to shunting on a white light, for instance, but at Exmouth Junction it was mainly done on a green light, a South Western custom. I suppose? After the fortnight in the yard I was back in the shed, rostered with a spare driver on the turn called ‘Prep 7’. In fact, we both prepared and disposed of engines on the ‘Prep 7’ turns, and on occasion would prepare an engine and take it down to Central, change over, bring another back and then dispose of it. Sometimes we were booked down passenger on an engine to relieve on another one then bring it up to the shed disposing of it, or vice versa. It added pleasure to the job to take an engine down and then watch it go away with its train, or to take a tired one off a train and up to the ‘Junction’ to be groomed for another turn of duty. On 18 June 1959 when I was with Les Lodge, the engine we collected turned out to be an ex LSWR ‘Greyhound’ ‘T9’ 4-4-0 No. 30711, which was then scrapped at Eastleigh two months later.

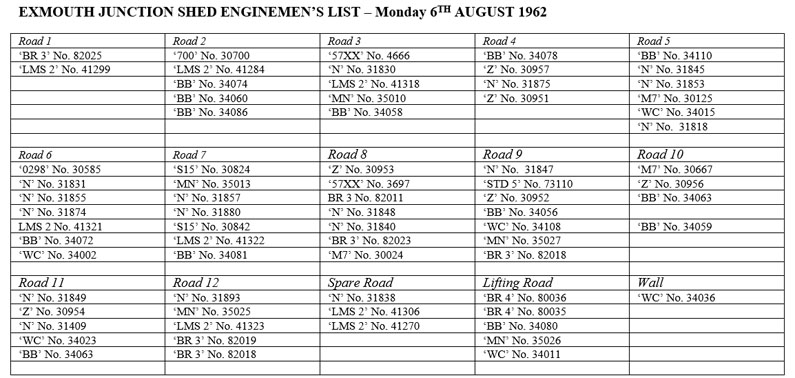

Besides learning the ropes I was settling into the life at the depot and sharing in the banter that goes on among locomen everywhere. Picture us on the 22.50 preparation turn. At around the mysterious hour of 02.00 we would have squared-up half our rostered engines and it was time for tea (PN. as it was called = Personal Needs). There were about four sets of men on at that time, as well as those preparing their own engines to go out early and those who had come in overnight and were waiting to start work. One night it had been blowing up a bit through the evening until finally, as we were sitting in the messroom, there came a terrific clap of thunder and the heavens opened. A few minutes later one of the preparation firemen came in absolutely soaked. Naturally, one of the chaps had to ask him if it was raining, and he said ‘What do you think’, or words to that effect! Then someone else said, ‘No, he asked for a refresher and he got one’! Then a voice enquired if that wasn't a thunderstorm he had heard, and back came the reply, ‘Yes, they were giving 'em out on the wireless last night, did you get one’? Among the locomen, in particular the younger element, I think there was more sense of fun about than there is today, and there were plenty of practical jokes. It was not at all unusual to be sitting at the long table in the messroom eating sandwiches and chatting when you would feel a thump on your foot. The biggest mistake would be to bend down and feel what it was, as it was probably a very dead partridge, or similar that someone had picked off the front of an engine. The chap sitting there with a suspiciously innocent look was probably the culprit. Now came the time to find the next recipient of the gift and some times an unwitting driver would go home with a fat bird in his saddlebag, or perhaps with half a coal-brick, or some nuts and bolts that had mysteriously found their way there from the scrap heap. One ‘anti-Guard’ technique in Exmouth Junction yard was employed when a guard arrived while the train he was to work was still being marshalled. The shunter would point out the allotted brake van to him and the guard would put his bag up into it while he went off to supervise, i.e. get in the way of shunting. Later on someone would politely tell the guard that he had been given the wrong van — one wanted else-where. At this point the shunting engine would he seen preparing to remove it. The guard would immediately dash into the van to retrieve his bag but of course it would not budge because someone had already carefully nailed it to the floor boards! Returning to Exmouth Junction shed itself; the accompanying chart is a record in detail of the engines on the depot at around 8 o'clock on the evening of Sunday, 5th August l962, and a copy of the sheet carried by the shed enginemen who had gone on duty at 4 o'clock that afternoon. Compared with the scene when I started at the shed in 1959 it differs by being three years later, obviously, although the pattern of workings is similar, but as the Monday was a Bank Holiday fewer freight services were around. The engines on each road are shown in order from the buffers with the time due off shed alongside. The shed engineman's job included seeing that all the engines got out in the right order, and the sheet shows that some were moved during the evening, the numbers being crossed off and re entered, i.e. No. 34059 was crossed off when she went out at 20.05. I don't have the matching roster that shows which duties the engines wore on. but I do know that No 30024 went out as carriage pilot at Central and No 35027 was on the 07.30 Exeter - Waterloo. You will notice that the busiest time for departures off shed was in the small hours of the morning. The engines out of use, for one reason or another, are marked by ‘X’, all of them being up against the stops. Among them were two Western Region pannier tanks and No. 30700, a ‘Black Motor', one of the last of the class. This engine was without a regular job and it was withdrawn in November 1962, although continuing to work on snow plough duties until finally leaving the shed on 31st December 1963. No 30585, one of the famous ‘0298’ Beattie well-tanks, had arrived from Wadebridge on 2nd August and No 30586 later joined it on the 16th August, the two leaving together on their last journey to Eastleigh on 22 August. Class ‘M7’ No. 30667, was previously No 30106 but was renumbered after overhaul in March 1961, the original No. 30667 having been scrapped in November 1960. All the 'Z' class tanks were on shed except No’s 30950 and 30955 which were probably out on the St Davids-Central bank. No. 30951 was booked out at 23.10, but the rest were 'on holiday' until Tuesday. The five engines marked 'ST' were in steam but with no booked duty, i.e. available as spares. The three down for 'WO Tues' were being prepared to have their boilers washed out and the three at the back of No 8 road were also probably awaiting washing out. Nearly all the seventy engines shown were actually at their home depot. The only visitors were No’s 30585 from Wadebridge, No. 30824 and 34059 from Salisbury. No. 31793 from Yeovil and 73110 from Nine Elms. An interesting point is that five of the engines on shed that night were destined to survive until the present day: ‘0298’ No 30585, ‘N’ No. 31874 and ‘West Countries’ No 34023 ‘Blackmoor Vale’ and ‘Battle of Britains’, No’s 34059 ‘Sir Archibald Sinclair’ and 34081 ‘93 Squadron’.

CHRONICLES FROM EXMOUTH JUNCTION‘THE EXMOUTH LINK’ When I had been at Exmouth Junction shed for a month I was told I would be taking my position in the Exmouth gang where I was to spend the next year. It was now well into the 1959 holiday season. When you moved from one depot to another the railway management, good people that they were, tried to let you take your holiday dates with you to avoid inconvenience. As my new regular mate went on his fortnight’s holiday immediately after mine, it was another month before we worked together. Albert was his name, but he was known to everyone as 'Moaner' because he was always quite happy as long as he had something to grumble about. A fireman was always good for a grumble, and often I would hear: '... never used to have this trouble with Buster'. Buster was my predecessor, and he must have been a paragon! Albert used to complain that of all the firemen on the railway they had given him a Cockney ‘barrow-boy’. He assured Ken the signalman at Sidmouth that if ever he wanted any spare parts for his car, which must have been some dreadful old banger in those pre-Test days. I would bring them down for him when I went home at weekends. They naturally maintained that all Londoners were ‘spivs’ or ‘barrow-boys’, whereas Albert generally referred to his other fireman as milk-boys. The older drivers traditionally addressed their firemen as 'Boy' - this put my hackles up a bit when I first heard it, after all I was over twenty-one, until I realised that it was a custom and not intended to be at all derogatory. I have heard a top link driver say casually to his fireman. 'Are you all right boy'? Although the latter was a grown man. The Exmouth branch opened on 1st May 1861, then the Sidmouth branch on 6 July 1874. Tipton St Johns to Budleigh Salterton on 15 May 1897 and Budleigh Salterton to Exmouth on 1st June 1903 with the group of lines forming a busy little system. The summer 1959 timetable showed 30 passenger trains daily each way between Exeter and Exmouth, with an extra one on Mondays and one between Exeter and Topsham only: 13 each way between Sidmouth Junction and Sidmouth and 14 on the Exmouth to Tipton line. Included in this lot were the through coaches from Waterloo which came off the 'Atlantic Coast Express' at Sidmouth Junction, divided at Tipton and went on to Sidmouth and Exmouth, and the corresponding return working. On the freight side there were daily workings from Sidmouth Junction to Sidmouth and back. Sidmouth Junction to Ottery St Mary and back. Exmouth Jn to Exmouth and back. Exmouth Junction to Newcourt Siding and back, and Exmouth lo Tipton (one way only, balanced by a return working down the main line). The Exmouth Link covered passenger and freight work on the branches and up the main line as far as Honiton as well as shunting at Central and St David's. There were 13 engine duties, and I have selected two of them to show what sort of work we had. The M7 0-4-4T on 611 duly started with a trip to Exmouth, then took a passenger train to Honiton and served as goods yard pilot, returning to the shed at midday for engine duties. Then it did more Exeter-Honiton passenger turns, shunted in Central goods yard and put in a spell shoving Up the St David's to Central bank: a fair day's work for an elderly engine. 614 duty was mostly spent between Exeter and Exmoulh and the engine went on the small shed at Exmouth during the afternoon, where it was serviced by Exmouth men. The Exmouth crews always preferred to work their engines chimney first to Exeter, while we had them facing towards Exmouth. There were 14 turns of duty for the men and the booking-on times were as follows: 03.23 (612 duty), 04.57 (614 duty), 05.25 (613 duty), 06.05 (611 duty), 07.25 (566 duty), 09.10 (548 duty), 09.41 (617 duty), 10.45 (613 duty), 11.55 (614 duty), 12.56 (612 duty), 13.05 (611 duty) 14.40 (615 duty), 15.40 (616 duty) and 16.25 (617 duty). The duty numbers are for Exmouth link engines except for No’s 566 and 548. When booking on at 07.25 the first job was to prepare the engine for the 08.42 to Plymouth and take it to Central. When relieved on that one we would take an engine, usually a Western pannier tank, to Exmouth and back. The 09.10 turn was an interesting one, we booked on at the Central to take 548 duty, which was the 09.35 up with a ‘West Country’. At Sidmouth Junction we changed to 610 duty, and worked the 10.12 freight to Ottery St Mary and back, then did three passenger trips to Sidmouth. The engine for this was a Standard 3 tank then, at 16.07 at Sidmouth Junction, we would change to 611 duty, the ‘M7’ on its way back from Honiton and finished at Central at 16.55, having covered three generations of locomotive design in the day's work. It is difficult to give an exact figure for the mileage covered in a turn, because of shunting at various places on freight trains and other such odds and ends, but the turn I have just described covered 64 miles. The 03.32 turn involved 62 miles. The 15.40 turn was 85 miles. This might not look much but, as it was all done up and down the ten mile Exmouth branch, with a couple of trips across to Tipton, it made a fair day's work for a fireman. You will see from the two duties that each engine was worked by at least two crews during the day and it was a recognised custom in the Exmouth gang for the early turn fireman to fill and trim the lamps, clean down the footplate, bunker front and windows and clean out the tool boxes. The late turn fireman then had nothing to do — apart from his normal duties which comprised firing the engine, taking water and hooking up and unhooking at terminal stations. One place where we did not un-hook ourselves was at Sidmouth Junction: there a shunter used to assist with the shunt movements. When we prepared an engine for the Exmouth line we usually made up the fire fairly well so that we could close up the bunker while running down to Central station while the fireman got a good start on the first part of his trip, out of Exeter Central up the gradient through St James Park tunnel, then over Exmouth Junction, shut off and run down into Polsloe Bridge. Having warmed the engine up we would then make up the fire a bit on the way to Exmouth and this would usually be enough. The idea was to do all the firing while running chimney first so as not to have to open the bunker when running backwards. An advantage here with a Standard tank was that if you did have to open the doors when bunker first there was a coal spray to keep the dust down: on a Drummond ‘M7’ you would have small whirlwinds of dust round your feet, resulting in dirty ankles. So we arranged to come back up without firing. We usually took water at Exmouth but not always: you could go down and back (and on occasions I have done two round trips) without taking water. That comprised 44 miles of stopping and starting with only 1.300 gallons of water in the tanks of an ‘M7’ or 1.500 in an BR 3 Standard tank. It was a good opportunity to learn boiler control, which means going all day without blowing off. Mind you there was more than one way to get water. When we were down in Central station shunting carriages or putting steam heat through them - the engine doing that duty was known as the hot water bottle - there might be a lull in the proceedings. With no one about there was a chance to take it easy for a spell. At such times the crew would save themselves trouble by purloining the hose used by the carriage cleaners and putting it in the tank to fill up the engine where it stood. Going across from Exmouth to Tipton there was little need to touch the fire at all and we usually went Exeter-Exmouth then Tipton-Exmouth on a tank of water. The footplate would be brushed and damped down with a spot of water in a bucket — a bucket of water was always carried on board for such uses. Then, on the way- back we would fire from Tipton to Exmouth, or front Tipton into Sidmouth. If we went up to Sidmouth Junction we would fire on the way back to Sidmouth. However, it was not always possible to restrict firing to chimney first running, and then there would be whirlpools of dust and so Albert would say to me. 'My wife complained again about dirty socks, and we never got as black as this when I was a fireman On fine mornings, running into Sidmouth on the early turn was always a pleasure. The rising mist would swirl across the line, bringing with it the scent of pine trees from Harpford woods, while if you kept a sharp look out you might see, as I did on several occasions, a shy wild deer dart away among the trees. Between Litlleham and Budleigh Salterton the line ran through a big estate, and we used to clout all sorts of birds, including pheasants and even swans. I have never been on an engine that clouted a swan, but I saw the remains, usually just a pile of feathers. Being a heavy bird, it was thrown to one side into the neighbouring fields to be picked clean by the buzzards. I never stopped to pick up a pheasant either, although you often heard of it. The story was that on this section, where game birds abounded, the platelayer used to have a pocket with a hole in it which he would fill with corn. As he walked along examining the track lengths the corn would trickle out and tempted by this buckshee snack pheasants would wander from the surrounding countryside on to the track. Along comes the train wallop - one pheasant for dinner. There was of course some competition from the train crews. If they saw it first and could get back there before the platelayer, the prize was theirs. It was on a fine Monday morning in my first year at Exmouth Junction that I got my nickname. I was along with Ernie B…… on 612 duty with an BR 3 standard tank. We booked on at 03.23 and went down to St Davids, did a bit of shunting then back to Central, more shunting there for an hour, and were light engine to Sidmouth Junction to work the goods into Sidmouth. We had time at Central to make a can of tea then set off at 06.15 in front of the 06.30 up Waterloo. As we went along, still being a stranger and not knowing the place too well, I made the fire up well. We passed Broad Clyst and came up the bank through the crossing gates near Rockebeare where you could sight the distant signal for Whimple, just as the sun was coming up a treat on that lovely morning. I had put a final bit on the fire so that it would be all right for half an hour's shunting at Sidmouth Junction, was mopping my brow and preparing to pour out a cup of tea. I indicated to Ernie that the distant was on, so he shut off and as the fire-door was shut and there was a fair amount of mixed live and green coal in the firebox, rather a lot of black smoke was produced. Old Ernie turned the blower on and opened the fire-door and said: 'What a Smokey Joe you are, look at it!' I looked, and there was a great black streamer following us for about a quarter of a mile along the track. After that we stopped at the home signal and waited for about a couple of minutes until hasty movements were seen in the signalbox and the signal arm came off. When we moved into the platform we discovered that the signalman had overlaid a bit that morning and had only just arrived in time to see us coming along. He wanted to know who was putting up smoke signals, so of course Ernie said. ‘Oh, that's my mate from London, he's a proper Smokey he is! After this and some more in the same vein he pulled the starter off and we went of hell for leather to keep out of the path of the 06.30, by now on its way. The name soon got around and stuck with me. I was quite content with it because if you have a nickname on the railway it shows that you are regarded as an individual - in other words, you have arrived. I caused a total eclipse of the sun at Exmouth one day on a Tipton job. We were on 614 duly, with the Drummond tank working down to Exmouth and then over to Tipton. I had been making the fire up on the way down - not in the best Dugald Drummond tradition, but then if he had thought of his engine crews he might have put a bunker spray on his tank engines. After changing tablets at Lympstone I put a bit more on the fire, while old Albert stood there as usual with his arm through the reversing lever, pulling away at his pipe and watching the scenery go by. As we came round past the old brickyard at Exmouth I shut both the fire-door and the half-door and swept round with the brush. I said to Albert. ‘Mind your feel', he moved, and must have knocked the lever catch for there followed one of those moments when everything takes place instantly - to make up for all the other times when nothing happens. Out came the lever into full-gear, with the regulator the best part of fully open. There was a terrific roar and up from the chimney went a volume of black smoke. Albert grabbed the regulator to shut it. I made to open the door, but by now I should have been ready to hand the tablet up to the Exmouth signalman. A hand appeared through the smoke, so I hung the tablet on it. Then we were able to get ourselves sorted out: fire-door wide open, knock the half door down, shut the damper and put the injector on as we ran into the station. Albert was still mumbling, ‘don’t know how it all happened’, and ‘blasted lever flying out’. A great, black cloud ascended over Exmouth station, where it hung for a while before passing over the beach and out across the bay. We saw the funny side of it but the signalman was not amused. After I had unhooked, run round the train and come up over the top to back into the Tipton side of the station he flagged us down to enquire ‘what the bloody hell we thought we were doing’? On another trip down to Sidmouth Junction I mentioned to Albert that I was wondering what lo get for my landlady's birthday. He said. ‘Why not some flowers? I'll tell Alan the porter at Sidmouth Junction, his mother works in a smallholding’. So the order went out. ‘Barrow boy wants some flowers', and sure enough the next day we noticed a barrow on the platform half hidden under a mountain of assorted flowers. Having finished shunting we found Alan. ‘Did you get those flowers’? ‘Yes, they're up on the barrow there, that'll be sixpence’! Flower power was nothing to this lot. I just about got to the engine with them and we made the ten-minute run with the cab completely full of flowers. I could hardly take them all home on my bike, so Albert, the foreman, the foreman's runner and I all went home with generous bunches of flowers that evening, for sixpence! I mentioned a freight working from Sidmouth Junction to Otterv St Mary: 10.12 down and 10.47 back. The working timetable for this train reads: ‘Take up empty water chums at Cadhay Gates’ for the down trip and ‘Set down churns of water at Cadhay Gates' for the return. Cadhay Gates was a level crossing with a keeper’s house without any piped water and this is how it got its water supply. Old Tojo was in charge there, he was a little on the timid side, and the engine crews used to ‘wind him up' a bit unnecessarily at times, because he would rise to the bait every time and that was how it was on the railway. Old Albert would have him scurrying about like the proverbial scalded cat. There was no winding gear on the gates, he had to push them across. Late one Saturday we were on the last Sidmouth trip: 21.50 depart Sidmouth Junction. 22.10 Sidmouth arrive. 22.20 depart and 22.41 back at the Junction. We pulled out of the junction, trotted away under the bridge and down the bank. Cadhay Gates distant was ‘on’. Old Albert said to me: ‘I expect Tojo's gone to bed and forgotten us’! We crept round the corner and the home signal was ‘on’. We stopped at it, right by the crossing gates. I got off and walking down, saw a light was on, so I peered in and found I was looking into old Tojo's living room. He was there with his wife, both sitting with cups of coffee in their hands, both glued to the telly. I tapped on the window! Tojo's hair stood on end when he looked round and saw the ‘Face at the Window’ looking in! He put down his mug and came out mumbling something that fortunately I couldn't understand, pulled the lever to release the gates, opened them and finally pulled the signal ‘off’. Old Albert crept forward, offering some encouraging words about where he'd been, not worrying about the poor train crews who had still to get home, and on we went. For some weeks after that Albert used to come down and shout to old Tojo. ‘Aren’t you in bed yet’ but nothing was ever said about that night, and that was also how it was on the railway. Since the Exmouth and Sidmouth lines were single track, there were tablets to change at the stations. The regulation was that when the fireman collected a tablet he read it out to the driver who would hear what the departure and destination on it were, so the fireman knew he had the right one. I always called across us soon as I had changed the tablet and would receive just a nod of satisfaction from the driver. When I joined the Exmouth gang I had not encountered tablets, as we used staffs on the Brighton line. When changing staffs the outgoing one was held hanging down between finger and thumb close to your body, while the other hand was extended to catch the incoming one between your fingers. On the other hand, a tablet is a round object carried in a pouch with a big leather covered wire hoop. On my first trip, at all the stops the box was at the south end of the station so on the way out the signalman came up and handed the tablet over. However I tied myself in knots on the way back. I shall always remember the sight of the signalman at Ottery St Mary as we ran in on my first attempt to change tablets on the move. I handed mine out the way I thought it should be handed, and he put his down on the platform and scratched his head! When we stopped at the platform end the driver said: ‘Did you get the tablet’? I said. ‘No, he put it down on the ground’. ‘What are you playing at’? ‘Well I didn't know how to pick the other one up’. Then the signalman came up. ‘However do you exchange tablets like that, fireman’? ‘I don't know’ I replied. ‘I was wondering how I was supposed to pick up the one you had on the floor.' So we had a couple of dummy runs while we stood there, a ‘crash’ course in tablet changing, but as luck would have it on the next run-in the signalman did not have the tablet ready in time and had to walk up the platform again. The following trip we made the exchange without hiatus - another case of learning the tricks of the trade quickly when really required! Although the ‘BR Class 3’ Standard tanks had a double side window, when running bunker-first the fireman leaned over the door to catch the tablet, because if you took it from out of the window it could swing round and smash the adjacent glass in the side window. At Exmouth, the Exeter line home signal had an indicator box showing which platform the train was to enter. On one afternoon trip down with Albert, as I handed the tablet to the signalman Albert shouted up to him, ‘there's no number in the indicator’. Straightaway the signalman replied, ‘what the dickens he you doin' in here then’? Which was correct, as an indicator signal with no indication showing should by the rule be regarded as at Danger. So Albert was one down and the next couple of trips on the footplate were a bit gloomy. Now Exmouth signalbox stood in the fork of the Exeter and Tipton lines outside the station, with a veranda across one end where the signalman stood to change tablets. The track layout allowed two trains to run in together without conflicting: for instance the 13.40 Tipton and the 13.42 Exeter arrivals often approached at the same time. Normally when that happened the driver of the Exeter train would hang back to enable the signalman to get both tablets. However, this afternoon as we were running in Albert suddenly said to me. 'If the signalman's not there throw it up on the veranda'. As I did this I looked across and saw the Tipton train alongside, by an amazing coincidence passing the box at the same moment! When we had stopped the porter appeared and asked. ‘Where's the tablet’? Albert said: ‘There was no signalman in the box when we came by so my mate put it up on the veranda’. The porter reported this back while we ran round our train. Up at the box again, the signalman reappeared and Albert blandly told him that if he wanted us to wait until he was ready to receive the tablet, that was fine, but the lost time would be down to him! One all! On the 4th January 1960, a new express was put on to give a quicker journey for homebound commuters from Exeter to Exmouth by running non-stop. The departure was at 17.45. Exmouth Junction (pass) 17.48. Topsham (pass) 17.54 and Exmouth arrive at 18.03.18 minutes in total as compared with the normal time of 25-28 minutes. The present day diesel service runs from St Davids and takes 28 minutes. Albert and I worked this train on its first week using No 82019 the first ‘BR 3’ at Exeter to be fitted with AWS: whether she was specially selected or not I don't know? The running times were: Monday and Tuesday - 18 minutes: Wednesday. 17 minutes: Thursday I was on a rest day and Friday - 16 minutes. Albert received a mention in the local press. I don't know how long this service continued as when I moved into the next link I lost touch with the daily happenings on the branch. An event that gave us real prominence in the local papers was the centenary of the opening of the line from Yeovil to Exeter Central, celebrated on 19 July 1960. The LSWR gate-entrance set No. 737 was brought down from Yeovil and paired with Beattie well-tank No. 30587, just arrived back from Eastleigh Works. This then made a commemorative run from Exmouth Junction sidings to the Central, calling at St James Park Halt to pick up passengers in period costume. The engine was driven by James Gumm and fired by Peter Wratten and on arrival they were greeted by the ‘Mayor Alderman’ P. F. Brooks, who was a goods yard foreman at Exmouth Junction and the ‘Sheriff Councillor’ W. A. Cox who was on the Western Region. There was an exhibition in the yard comprising Beattie 0-4-2WT class No. 30587, plus an Adams 0415 class 4-4-2T No. 30582 and a Bulleid ‘Merchant Navy’ class No. 35003 ‘Royal Mail’, and it rained! By this time I had moved up into the ‘Junior Spare Link’ and only saw Exmouth on irregular occasions. On 11 June 1960 I had my last trip with old Albert and by now I'd got to know him a lot better. My place in the Exmouth Link was taken by young Bernard D…… who doubtless heard I was a wonderful fireman by comparison with him. Bernard was the lad who, besides soaking Albert once or twice by overfilling the engine tank and trod on his pipe while it was still in his mouth! Albert was climbing down the cab steps at the time and Bernard followed rather too closely after him!

CHRONICLES FROM EXMOUTH JUNCTION‘GOING SPARE’ Continuing my career as a fireman at Exmouth Junction Motive Power Depot, on Monday 13 June 1960 I moved into the Junior Spare Link. As the title implies, the men in this gang were available to cover staff sickness, holidays and all kinds of extra trains. You could expect to go anywhere, on any type of engine, at any time. So men in that link had to be experienced enough to tackle a wide range of duties, and would gain detailed knowledge of all the work in the depot. This would stand them in good stead when they progressed to the senior links. The lodging away turns were also rostered to the spare link. In the Exmouth link, most of the work had involved running up and down the branch lines mainly working passenger trains with one or two goods trains thrown in. As it happened I had spent the evening of the previous Monday 6 June, on shed duties which included helping to dispose of two famous engines: ‘Merchant Navy’ 4 6-2 No’s 35001 ‘Channel Packet’ and 35028 ‘Clan Line’. I was now well and truly in at the deep end, kicking off with Preparation duty No. 11. This meant a night's work of disposing of three engines and then, preparing three. The first job was generally to dispose of the ‘Duck’, the ‘Z’ class 0-8-0T which came in off the yard at around 23.00 having been out there since the early hours of the morning. Then we had two 'West Country’s to square up and two to prepare - one of which would be for the newspaper train and the other for an up service. Finally, we got an ‘N’ 2-6-0 ready for an early morning down goods train. That first night I was on to dispose of ‘Z’ No. 30955 then light pacifics No’s 34109 ‘Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory’ and 34065 Hurricane, and to prepare No’s 34069 ‘Hawkinge’ and 34065 ‘Hurricane’ and finally ‘N’ No. 31837. When you 'disposed' an engine, it meant that you joined it on the ash pit and immediately got up on the tender to put the ‘pipe’ in, while the driver turned the water on gently. While the driver was examining the engine for defects, you put the blower on, found a 3/4” spanner, shovel and brush, and cleared out the smokebox. After sweeping down the front end you climbed into the cab and got out the clinker shovel (or slice), dart and pricker to clean the fire. You cleaned half the grate area at a time: some depots did the front and back halves, but we always cleaned from side to side. On BR Standard locomotives with their drop grates, you pushed the fire forward, dropped the clinker from the back half, then pulled the fire back and dropped the front half. While doing this, it was your job to check the condition of the tube plate, brick arch and fire bars. The driver might lend a hand with the fire if he wished. Next, you went underneath and made sure that the ash pans were clear. By now the tank would be full, so out with the pipe, go up for coal turn the engine if required and stable it, then start on the next one! Usually you would put an engine in the shed with a little fire left in made up right under the door. It could then be left safely for the firelighter to keep an occasional eye on the fire, saving him from having to carry shovels of hot coal and loads of wood and mess about lighting up again. However if an engine had a long stay on the shed, the fire would be thrown out. Occasionally, you might strike lucky on disposal and get a ‘soft number’; this meant that someone else had already done the fire and all you had to do was to coal and turn the engine. When preparing an engine, you would climb aboard, give the handbrake a tug to ensure that it was on, sec that there was enough water in the boiler and look at the state of the fire. You collected the engine oil, thick oil and paraffin cans and took them to the stores to be filled with the engine's ration then filled a feeder for the driver, who had started his examination and oiling. You filled the sandboxes, tightened the smokebox door, trimmed and filled the lamps, lit them if needed, and checked the tools: bucket, brush, spanners, fire-irons, coal pick. shovel, gauge glasses, detonators, red flags, disc boards, and the rest. If the engine was due to go out shortly, you made up the fire, if not you would leave the fire and the driver would leave the trimmings out. Then when a crew came on later, booked to prepare the engine, they would make up the fire and take coal and water before departing. Alternatively, the engine might be wanted by the foreman as a spare, in this case it would be tucked in under the wall and marked ‘Steam’ on the List until something turned up for it to work. The List was the shed's locomotive duty roster, showing which engine was to do what for a period of 24 hours. The level of activity on the pits varied, of course. Nights were busy, evenings were quieter and at weekends, there were just a few engines coming in from several directions to be squared up for Monday's jobs. On summer Saturdays, however, all hell was let loose. We would be faced with such a procession of engines coming in on shed for servicing that all we could do was to grab each one. wind it up and send it back out again, then on to the next one! After a week on this work I was out on the yard pilot again with Alf P…… Alf always called his fireman ‘Comrade’ and he was a star-gazer. One of the delights on a starry night was that during pauses in the shunting work Alf would give you a lecture on the heavens and their contents, the moon and the stars, the Plough, Great Bear, Kite and the rest. If you showed an interest in astronomy, Alf would be voluble about his other favourite subjects, one of which I recall was photography. In this way the shift would pass by quite quickly. The ‘Night of the Haunted Office' occurred at about this time. I was on at 22.50 with my regular mate young Bob D…….. (not to be confused with his father, Bob (who was also a driver). He had a feeder of oil and a duck lamp (the paraffin lamp that drivers use) and started going round the ‘West Country’ we were preparing for the 02.06 to Ilfracombe. I went down to the stores to draw the rest of the oil and as I came back I saw him jump off the front end (the location of the lubricators on an original Bulleid) and scuttle off rather furtively. A little later I was back at the stores, just in front of me the Running Foreman who happily wandered into the Foreman's office, only to dash out seconds later with a horrible scream! I ran up to help him in whatever catastrophe had struck him. There, stretched out over his desk and supported by the desk lamp, with wings outspread and an unblinking stare in its eves was an owl. A ‘dead’ owl! The foreman had come face to face with it when he walked in and switched on the light! When I returned to my engine and remarked to my mate that the foreman had just had a fright, he didn't say anything, but just went off down the side of the engine chuckling to himself, I then put two and two together! Incidentally, it was Bob ‘senior’ who once picked up a buzzard on the front of an engine and found it was still alive. He took it home and kept it in his garden shed for a fortnight until it had recovered from its injuries. On 21st June Bob and I found that we were mysteriously booked for a 03.40 ‘Special'. ‘Light engine to St David's' was all that was said. The whole business had an air of mystery, either nobody really knew anything about it or else thought that we were briefed as to what the job involved and so didn't bother to tell us. We didn't know, and somehow it did not seem polite to ask. ‘Battle of Britain’ 4 6-2 No. 34076 ‘46 Squadron’ was the engine and she was spotlessly clean. We had come on duty in the usual style of spare men, with dirty overalls and boots, ready for a night's session on the pits preparing engines. Anyway, we got her ready, and the foreman came out and asked, ‘Have you got the headboards’? ‘Yes’, I said, we had all the headboards we wanted, and then he said, ‘Don't go making a noise down there, blowing off or anything like that’! Not knowing what to make of this we shrugged our shoulders and trundled off down to St David’s where all was peace and quiet. In came a Western Region train with a ‘Warship’ diesel at its head and then up came Inspector Smith who enquired, ‘Steam heater working all right’? ‘Well, I dunno, we haven't tried it’. (Steam heating on a warm night in June?) I got down and looked around: steam pipes on each end, yes, but nothing between engine and tender. ‘I’ll go and see what I can do’, so saying the Inspector who disappeared into the Western shed to find steam heating pipes for Southern engine! Next came a shunter, ‘Up on to this lot driver’, he says, ‘that'll be your train’. We backed on to the train, tender-first and the Inspector came back saving: 'I can’t get a pipe over there’. My mate said: 'Well now what is this all about’? ‘Oh we're working the Royal Train’, came the reply’!!! He was right, there were four immaculately turned out coaches behind and Princess Alexandra was asleep back there. We were told there would be no whistles, when the signal came off the guard would give us a green light from the back and we were to go to Seaton Junction at the normal permitted speed for tender first running. It was a beautiful morning, the dew was settling a treat on the rails and as with most Bulleid pacifics, the tender sandbox were damp and the sanders not working. So away we went – chuffety, chuffety chchchchchchchuff, chuffety, chuffety, chchchchchchuff - and came to a stand, right between the two sets of catch-points on the 1 in 37 incline of St David's bank! What could we do? What would be our fate? The poor little fireman, they might not ever bother themselves with giving him the sack, but the driver would probably be put back the shed, never to see sunlight again, whilst the Inspector would be hung, drawn and quartered in the Cathedral yard at dawn! Anyway, I proceeded to the signalbox at the bottom of the bank to tell the signalman (or the ‘Bobby’ - well it was the Western!) that we had stuck, and daren't move because of the catch-points, and required assistance. As always, no assistance was in sight, nothing was available on St David's shed the only locomotive that could be summoned from anywhere was a ‘700’ 0-6-0 that was quietly shunting in Yeoford yard. It was ordered post-haste to St David's to bank the Royal Train. On arrival the Inspector instructed the crews that, at a given signal, both drivers were to open their regulators together and so it was hoped move off. The signal was given and we moved, very slowly at first, but the ‘700’ seemed to be doing its stuff at the back and got us into the tunnel. There the Bulleid found some adhesion on the dry rail. We left the ‘700’ under the lights of the footbridge at Central as we gained speed to attack the next uphill stretch into Blackboy Road Tunnel. We arrived at Seaton Junction, I forget how late we were - ran round the train and moved into one of the down sidings furthest away from the main line. After we had settled down I decided to look round the engine and put up the head-code. No sooner had I touched the ground when I became aware of a presence behind me. I turned around hastily, knowing that my mate was or the footplate, to see an officer of the law, handcuffs at the ready, asking me where I had come from! A whispered discussion ensued in which I told him who I was and hat I was doing, then he accompanied me round the engine to make sure that I was what I said and did what I did. Princess Alexandra was travelling to Honiton for an engagement connected with a regiment stationed there, so when the time came we worked the train forward to Honiton station and stopped in the platform. I didn't know where the red carpet was and I don't think my mate knew either, however the Inspector told him where to stop. After the Royal party had detrained, we proceeded with engine and empty coaches to Exeter Central. where we were relieved. The coaches were placed in the carriage cleaning shed, I don't know what they did with the Princess, because I went home to bed as I was on at 04.15 the next morning. That episode took place on a Tuesday morning, the next Saturday I went passenger to Barnstaple Junction to work the station pilot with Drummond ‘M7’ 0-4-4T No. 30254. Jobs like that provided the opportunity to pick up some knowledge of the road, track layout and workings at various places, and this would be useful later on as a driver. Then I went on a fortnight's holiday, during which I began my association with the world of railway preservation, with a couple of days on the Bluebell Railway. My diary records I lit up the Terrier ‘Stepney’ and acted as firing instructor on a couple of trips. My appearances were infrequent, since it involved travelling from Exeter, but I believe I played a part in securing the Adams ‘Radial’ tank No. 30583 for preservation, when she finished on the Lyme Regis branch the next year. My next turn was on No. 30583 and the date was the 1st July 1960. We booked on at 12.45 at Exeter Central, then caught the 13.10 stopping train and relieved the crew at Axminster. Then we did 74 miles up and down the 6.1/2 mile branch. We lodged the night and the routine was as follows, on the last but one trip you would clean the fire. When you arrived at Lyme Regis on the last trip, you went at once to the cabin to put the kettle on. The cabin was a little place on the end of the goods shed, equipped with three bunks, a sink, cold water tap, a gas cooker, an old fashioned stove and a great iron kettle that held about two gallons. You would bring the engine on to the shed, pull the fire under the door, take water, fill up the boiler and hand her over to the fire-lighter, steam-raiser, come shed labourer, actually he was a Midlander, called ‘Old Tom’. His job was to unload the coal wagon on the dock, chop firewood if the engine had to be lit up (which wasn't usual), keep the place generally tidy and call you up in the morning. When you had squared up the engine, the kettle would be hot enough for a wash before you walked down to the town to visit the pub and the fish and chip shop. By the time you got back to the shed, the kettle would be boiling, so you could make a cup of tea before going to bed. Normally, the resident fireman would do the next morning's duties and you would book on at say 12.15 to be relieved in the evening by another fireman, who travelled up on the 19.50 from Exeter. On my first stint this relief man did not arrive, so I had to finish the day. square up the engine, lodge for another night and work the early turn. Then I went back to Exmouth Junction in the morning. On reporting back at the shed I finished the day’s work by preparing a ‘West Country' for the 12.30 Exeter Central - Waterloo. On 18 July Adams 4-4-2T No 30582 came back from Eastleigh Works ‘half-soled and heeled', as the saying goes, in time for the Salisbury-Exeter line centenary exhibition. I was then working a week on the Exmouth branch with old Ernie L……. . Ernie used to keep bees, so getting on with him meant learning all about bees, how honey was made and so on. Perhaps you would finish the week with a little reward ‘Here, you try a jar of this, me boy’, in this way the railway was kept running smoothly. Back on the shed for more preparation and disposal turns. While I was about the shed I used to keep an eye out for unfamiliar engines that might appear. The Meldon stone trains, for instance, often produced an ‘N15’ ‘Arthur’. No 30781 ‘Sir Aglovale’ on 18 July, No. 30450 ‘Sir Kay’ on 19 July, No. 30451 ‘Sir Lamorak’ on 20 July, No. 30457 ‘Sir Bedivere’ on 21 July, ‘H15’ 4-6-0 No. 30522 on 22 July and No. 30453 ‘King Arthur’ on 26 July. Beattie 2-4-0WT No. 30585 came up from Wadebridge (72F) on 20 July and left for Salisbury the next day, while No 30587 went down in her place. Other engines I noted were ‘57xx' 0-6-0PT No. 9764 on 26 July: No 6842 ‘Nunhold Grange’ with an excursion from Banbury on 4 August. ‘G6' 0-6-0T No DS3152 formerly No 30272 and lately the Meldon Quarry shunter, left for Salisbury on 9 August. ‘2884’ No. 2894 on 22 August. ‘BR 4’ 2-6-0 No. 76018 in from Yeovil with an engineers' inspection train (coach DS291) on 1 September. Ivatt – ‘LMS 2’ 2-6-2T No. 41297 in from Salisbury on 16 September (this engine was to be tried out on the Lyme Regis branch): ‘57XX’ 0-6-0PT No. 9732 on 12 October. ‘LN’ No. 30855 ‘Robert Blake’ on a football special on 22 October Light pacific ‘Battle of Britain’ No. 34058 ‘Sir Frederick Pile’ (fresh from rebuilding) on 22 November. ‘G6’ 0-6-0T No. 30236 (renumbered DS 682) in from Yeovil on 14 December on the way down to Meldon Quarry : ‘02’ 0-4-4T No 30199 up from Meldon on 29 December. ‘LN’ No. 30853 ‘Sir Richard Grenville’ on 5 January 1961 and No. 30859 ‘Lord Hood’, the next day: ‘Ul’ No. 31901 on 12 June, together with ‘BR Standard 5’ No. 73114 ‘Etarre’ (70A). ‘Ul’ No. 31909 on 19 June and ‘WD’ 2-8-0 No. 90188 seen on the 04.10 to Bristol on 21 June. On 27 July 1960 I went up on another Lyme Regis trip for two days, on the second night taking the relief fireman's last trip for him so that he could go home for the night. We had No. 30582 and it was a pleasure of working on a clean engine. I got back to Exmouth Junction on the Friday to join another fireman, who had just come back from Bude. Between us we filled the sandboxes on No’s 30125. 30317, 30327, 30584, 30670, 30843, 30957, 31841, 34002 and 82019, after that the foreman said we could both go home! Another interesting Lyme Regis job involved changing over the branch engine on a Saturday. You took the fresh engine ‘light’ over the 27 miles to Axminster, did a turn down the branch and then brought back the other engine after its week of duty. Some readers may remember that during the summer, when two engines were on the branch, they double-headed the trains conveying through coaches from Waterloo. At that time there were two up through trains, 09.00 and 15.05 and two down, the 08.05 and 10.45 from Waterloo. On one such occasion, we used the Adams tank on a ballast train. Instead of coming straight home, we went from Sidmouth Junction to Tipton. There, we collected a couple of ballast wagons and propelled them round to Newton Poppleford to unload the ballast. We returned the wagons to Tipton and continued light engine to Exmouth Junction. The Adams 4-4-2Ts had been working the line for forty years, another survival of the ‘old railway' and one that was coming to an end. On 18 September I960. Ivatt - ‘LMS ‘2’ 2-6-2T No 41297 a Barnstaple Junction engine (72E), came down for trial runs. These were generally successful, and after the track had been eased in places the Ivatt tanks came into regular use from the beginning of 1961. Adams 4-4-2T No 30584 was withdrawn on 28 January. No 30582 worked her last turn on 5 May and then lay at Exmouth Junction shed until leaving for Eastleigh at 10.40 on 18 July. No 30583 finished on 21 April, but left not for scrapping but for a new life. Departing Exmouth Junction on Thursday the 1 June at 07.05 she stopped for twenty minutes at Seaton Junction, took water at Axminster (08.15). Yeovil Junction (09.05). Templecombe (09.30) and Gillingham (09.50) waited at Tisbury for an hour and reached Salisbury at 12.05. From there she continued onto Eastleigh. Her next move was as LSWR No. 488 of the Bluebell Railway, from Eastleigh shed to Brighton shed on the afternoon of 9 July. Three days later, she was on the Bluebell, ready to start another phase of her career, and has now spent more years there than on the Lyme Regis branch. Back to 1960, and I was widening my experience. On Saturday 30 July I went on loan to Okehampton and worked 127 miles on engines No’s 82019 and 31860, returning to Exeter with a goods train. On 17 August I was back at Okehampton this time on Drummond ‘T9' 4-4-0 No. 30313 covering 62 miles to Bude and back and disposing of it at Okehampton shed. The next day I did an Okehampton to Launceston trip. I was also on ‘T9’s No’s 30718/19 that week (both these locomotives plus 30338 were previously at 70A in 1957). To someone interested in railways and railway history it was an added pleasure to be working on engines as famous as the ‘T9’s. At that time, we had eight of the remaining fourteen ‘T9’s No’s 30313/38/709/15/17/18/19 and 29. In March 1961 we also received No. 30120. Besides the North Devon and Cornwall jobs, a ‘T9’ was frequently rostered for the Newcourt goods. This involved a trip Newcourt Siding, which served a naval depot half-way to Topsham on the Exmouth branch, and to Broad Clyst where there was a permanent way engineering depot. This job also saw the use of the six-coupled 0-6-0 version of the design, the ‘700’ class. On 30 August we had No. 30317, then the next day No. 30700 and for change, on 2 September, an ‘S15’ 4-6-0. Among many different jobs, on 11 August I worked one of my few turns with a ‘BR Standard 4’ 2-6-0. I booked on at the Central, then rode passenger to Yeovil and relieved on No. 76005 and worked a stopping goods to Crewkerne and Axminster - 20 miles. We shunted there, worked back to Yeovil and I came home passenger. On 3 September. I covered 23 miles on an ‘N15’ (‘King Arthur’) with the 11.12 stopping train as far as Seaton Junction, returning with an ‘S15’ on the down train. On 6 September. I was booked on ‘Spl 103’, a troop train - on at 14.00 then out to Halwill Junction, run round and back to Okehampton a total of 52 miles on ‘West Country’ No 34033 ‘Chard’. Troop train specials were frequent jobs for the ‘Spare Gang’. Usually when the train arrived at its destination, the troops would detrain and go out on to the moors for manoeuvres. One night. I worked my first trip over the whole of the Salisbury-Exeter line. I booked on at 17.39 with Jim G…. and we rode passenger to Salisbury. Our engine ‘H15’ 4-6-0 No. 30523 was ready for us and we coupled on to the sleeper train - wooden sleepers that is, from Redbridge Works - and took it to Exmouth Junction. The next night we were on the same turn, with ‘U’ 2-6-0 No. 31637. Incidentally, this was originally a South Eastern engine, so the cab controls were arranged for right-hand driving and as such I was firing on the other side of the footplate. A point that car drivers may not appreciate that on the railway there arc no street-lights and no bright headlights on the engine. At night, the view ahead is pitch-black and you depend entirely on the knowledge of the line ahead to keep a track of your progress. On that particular trip I recall as we rolled through the deserted, dark countryside that I walked over to the driver and said in a broad London accent, ‘Here Jim it ain't ‘alf dark round 'ere’! He replied in broad Dorset, ‘What do yo-mean’? ‘Well up in London when you was out is the dark, you didn't go very far before you'd see some houses around and could pick out some landmarks, but there ain't many houses about, or anything, out here’! For years after that, whenever Jim saw me he would mimic, ‘Here, it ain't ‘alf dark 'ere, there ain't many houses about’! Ted ‘Smokey’ Crawforth – 72A

|

|

Site sponsored/maintained by SVSFilm © 2017 ... Go to SVS Film Index Go to Nine Elms Main Index - "Light to Loco" |