‘DOWN STEWARTS LANE WAY’

by RICHARD HARRY NORMAN HARDY

Foreword

The day that I first met Richard Hardy was my good fortune for it became a friendship that I cherish to this day. Our numerous chats on matters concerning railways, particularly the Southern of course, were a pleasure and indeed an education.

Richard was also known as ‘Dick’ to many of his numerous friends.

His attendance at the ‘Nine Elms Enginemen’s Reunion’ on several occasions left him in awe of those that wanted to talk with him. On receiving his initial invitation he said “But I won’t know anyone”! How wrong he was, he later told me that he never stopped talking, what a surprise!

Our later mutual collaboration with the ‘Friends of the National Railway Museum’ chairman - Dr. Ian Harrison - was another pleasure and success. The subsequent fund-raising campaign to restore the then rather neglected ‘Battle of Britain’ No. 34051 ‘Winston Churchill’ meant working closely together.

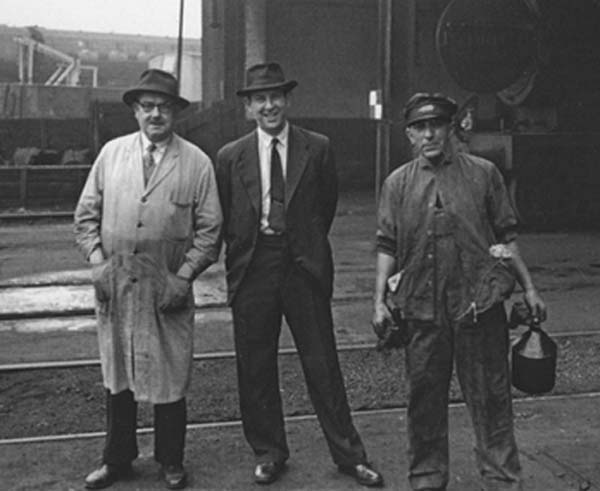

Richard Hardy (centre) is with Stewarts Lane driver Sammy Gingell (right). Photo - Jim Lester collection

During these times I had the idea of reprinting an interesting article that he had produced many years ago that covered the time that he was the Stewarts Lane Shedmaster. My only regret is the retrospective view back to those times that he intended to write sadly never happened.

Whatever many of his memories survive for us all to reflect upon, we are indebted to him, his life and times.

Jim Lester -70A

DOWN STEWARTS LANE WAY – RICHARD HARDY

My first impression of the Southern Region was its family atmosphere and the keenness of the majority of its staff. Also particularly noticeable was the wish, as far as my section of the railway was concerned, to keep time and arrive to time at all costs; and this is, of course, a very laudable and a very desirable principle.

My depot was responsible for a large amount of the most important classes of work on the Eastern Section - the Kent Coast passenger excursion work, the boat traffic, and, of course, the “Golden Arrow”, perhaps the most opulent and romantic train then running. On the Central side, we handled some of the morning and evening business trains, including the popular 5.50pm Victoria to Tunbridge Wells and 6.10pm Victoria to Uckfield. Both these jobs meant hard work, as far as the engines were concerned, and there was little to throw away even if things were going well on the footplate. The 6.10pm was the subject occasionally of complaints from the regular travellers and things certainly went wrong from time to time, but this was not for want of trying on the part of any of us, either in the shed or on the road.

The largest locomotives at the depot were the ‘Merchant Navy’ class Pacifics. When in good order these engines, despite all that has been said and written about them and against them, are fully the equal on the road of the LNER Class ‘A4’ Pacifies; having worked for many miles on both these classes, I feel that I am qualified to make this statement. The freedom of movement of all the Bulleid Pacifics has to be felt to be believed, and when worked heavily, their capacity to make steam is very fine indeed. Firing these engines is not a difficult nor a laborious job, as very little coal is required in the front corners of the firebox; contrary to the accepted rules on firing engines with wide fireboxes, some of these Pacifies will take a thin fire, although some, and I think perhaps the majority, prefer a heavy fire under the fire-hole door. Indeed, on a ‘Merchant Navy’ I do not recall having a bad trip. When working on no more than 15 per cent cut-off, these engines will run at very high speed along the straight from Ashford to Tonbridge.

On the ‘West Country’ Pacifics also I have had many good trips, and perhaps the one I remember the most vividly was an occasion on the 2.30pm Dover to Victoria via Chatham with No 34091 ‘Weymouth’. We had come down on the 10am “Continental” from Victoria to Dover on hard coal and had 280 lb of steam all the way. Notwithstanding two signal stops and two speed orders for track repairs, we were only a minute late into Dover.

Here a relief crew took on a tub or two of Snowdown coal, which is a soft Kentish product, and made up a fresh fire on top of a very low fire, a most unwise proceeding with soft coal.

When we came to leave with the train, we had what appeared to be a nice fire, but despite me livening it up with the fire-irons we were four minutes down at Shepherdswell, with no more than 100 lb of steam on the gauge and an inch of water in the glass. The tare load of 446 tons was a very heavy one for a light Pacific over the Chatham road, but by really fine enginemanship we topped the long 1 in 100 climb to Sole Street (where the fire showed some signs of coming to life) on time, with 200 lb of steam, and this was the most we saw all the way up. So No. 34091, with Driver Brewer of Stewarts Lane in charge, gave an excellent example of how time could be regained by taking advantage of the rise and fall of the road and regaining steam with the minimum of waste.

But not all Kent coal is dull; on the contrary, the best grades are very good once the art of firing with them has been mastered. Hard coal smokes much longer than soft for every firing, whereas Kent coal smokes heavily for a very short period and then must be left alone until judgment tells one the next time to fire. I learnt this by experience very soon after coming on the Southern on an ‘King Arthur Class’ (‘N15’) 4-6-0 No 30766, ‘Sir Geraint’ on which I was riding from Faversham to Victoria. After Chatham I was doing the firing up Sole Street bank and in accordance with my LNER and Eastern Region training I was watching the chimney top after each firing; directly the smoke had cleared, I was putting four or five more shovelfuls round the firebox. Halfway up the bank, the needle began to hang, and my next charge did not produce any smoke, nor did the next. Immediately I reached for the poker and found, to my alarm, what I certainly did not expect to find - a box full of fire. Without any further attention this took the engine from half-way up the Sole Street bank right through to Victoria, and from that day onwards I realised that the application of soft Kent coal calls for constant attention and thought to get the best results.

Mention of No. 30766 brings me to the ‘King Arthur’ class. During 1952 I felt that these engines had fallen somewhat into disrepute and we decided to nominate such engines as No’s 770 ‘Sir Prianius’, 771 ‘Sir Sagramore’, 766 ‘Sir Geraint’ and 768 ‘Sir Balin’ to certain turns, so that the engines could be well cared for and cleaned daily. A ‘King Arthur’ is a very robust machine, mechanically sound as to design, and it gives little trouble provided that the valves and pistons are examined periodically, and the injectors are properly maintained. The right-hand injector is of the old Davies & Metcalfe “F” non-automatic exhaust pattern, which requires skill for correct operation and maintenance. During the last two years, I venture to suggest, the King Arthur’s have done as good work as any during the course of their lives. On the 3.35pm from Victoria to Ramsgate, manned by the enginemen in No 2 Link at Stewarts Lane, No 768 has put up some first-class performances. This engine has always been kept beautifully clean and reflects great credit on the cleaning staff responsible, as well as the enginemen in this link, particularly Driver Sam Gingell, who has spent many hours cleaning the footplate.

On the road, No 768 can be worked satisfactorily on very short cut-offs, and with a wide open regulator, and can stand very heavy working on the banks without draining the boiler. A ‘King Arthur’ requires a good fire under the fire-hole door and a thin fire at the front of the firebox. The fire-hole door itself has a hinged flap which, when in position, leaves a very small slit through which one can fire with light shovelfuls of coal broken up small. This half-door is of tremendous value on a heavy train, when the engine is being worked to its limit and it is desirable to reduce to a minimum the quantity of cold air entering the firebox when firing. ‘A ‘King Arthur’ may perhaps be a little slow off the mark, especially on the banks, but these engines have much to commend them.

It seems fashionable in some, quarters to decry the methods of the old South Eastern & Chatham Railway, but so far as engines are concerned I am bound to say that I have a great admiration for those of the former SE & CR and for the staff which came from that railway. Now both the London & South Western and London, Brighton & South Coast Railways were most efficiently run and their locomotive stock beautifully maintained, and some of their enginemen, with their stiff white collars and their bow ties, created an impression, and rightly so, of dignity and efficiency. On the old SE & CR, at any rate after the First World War, there was comparatively little spit and polish, and chokers were more common than collars and ties. But I never encountered such men as those of the one-time SE & CR for keeping the job going during the busy and rough summer months.

There was nothing that these men would not tackle. On a summer Saturday, we have managed to get a seemingly endless collection of locomotives off the shed to time and away from Victoria. These engines, largely ex- SE & CR or Maunsell designs, have gone down to the coast, some of them considerably overloaded, and have come back again with very little trouble into Stewarts Lane shed on a Saturday night. Here a very limited number of men, guided by Running Foremen whose one object in life is punctuality, have got these engines put away and ready for another mad rush on the Sunday morning; and so it goes on throughout the summer.

On a summer Saturday, my duties would bring me to the shed at about 6.30am, and there I would find the night Running Foremen very much ready for home. I do not mean that they would have their feet up, far from it. It is because they have had a really busy night.

During the night the shed staff have had the boiler filling pipes in as many tenders as possible to top them up; the shed enginemen have marshalled the engines in their order of going out and the engines have been booked out as far as possible with the best engines on the hardest duties; the repair staff have been getting as far forward as possible with drivers’ bookings and other repairs. A number of the engines have been prepared, some by the trainmen, others by preparation sets, and it has been my job to see, in conjunction with the Running Foreman on duty, the repair staff, and the locomotive shunters, that the engines leave in the right order and at the right time.

We must constantly be in touch with our Locomotive Foreman at Victoria, and must keep our eyes open and our wits about us for dealing with any of the little points that arise. We know that Driver B—, on duty at 8am for 9am off the shed, has Engine No 774 ‘Sir Gaheris’ and he thinks she is a rough old tub. We know she is and we expect that, as a mild protest, he will insist on going round for coal at the last moment; so before he goes we kindly suggest that he may want some coal before setting off. He says quite plainly (Battersea fashion) that he doesn't want coal, passes some wisecrack about 774, and leaves the shed to time. A little later on Driver C— comes on duty, and we know that lie always likes to be off the shed at the last moment, really because he has a sense of humour and likes to keep us strung up for as long as he can. Consequently, we take no notice, and do not even acknowledge his existence. Mystified, he comes to the Foreman's office, to be rung out "right time".

The morning soon goes, and the afternoon arrives. Now the procedure is reversed; the country engines and our early engines start coming in, to be turned round again for further workings in the evenings to the coast. I used to take a trip to Faversham or Whitstable on the footplate during the afternoon on an ‘N’ class, perhaps, and return on a 'D1’ with a nine-coach or ten-coach train. The ‘Dl’ is a Maunsell masterpiece; for their size, there arc very few engines in the country to touch the ‘Dl’ 4-4-0s, but they must be fired carefully to get the best results. During the summer young and inexperienced firemen have to work on the Kent Coast trains, because of the intensity of the traffic, and the consequent necessity for all possible men to be available for train work. So I have felt it necessary, as far as I could, to ride with these youngsters and give them "moral support" and practical assistance to help them in their duties. Most of our young men, I may add, are very receptive, once their interest has been captured. A ‘Dl’ or an ‘El’ must be fired heavily under the fire-hole and very lightly at the front, and they can be driven with equal success either with short cut-off and wide regulator or long cut-off and the first port of the regulator. Sole Street bank can be a gruelling business, but the heavy blast on the fire would bring the fire really to life, and the steam pressure needle on old 1749 would stand over on the 180 lb mark. Once over the top, the engine would fly, and 75mph through Farningham Road would be reached with ease. The brick arches on these engines are set very low; consequently, when one was firing, the back hand has to be kept well up, or the coal would be shot on top of the arch instead of underneath it, with inevitable shortage of steam.

Eventually Victoria would be reached and I would put in a little time with the Locomotive Foreman, then returning to the shed, ready for the evening rush, and reaching home perhaps by 10 o'clock at night. After this, Sunday morning and a similar procedure arrive very soon indeed!

One of the first locomotives built to Maunsell's designs was the ‘N’ class 2-6-0 No 810, now 31810. This one is at Stewarts Lane and is typical of a class of engine that is of great operating value. In fact, the ‘N’ class, to my mind, is comparable to the old Great Northern ‘K2’ "Ragtimers" on the late LNER; but in my experience the Southern Moguls, though equal to the ‘K2’s in maintenance, are greatly superior in performance. The Maunsell 2-6-0’s do a large amount of passenger work in the summer months, working most of the semi-fast excursions on the Ramsgate road and many of the through trains from Willesden to Bognor, Little- Hampton, Eastbourne, and the Kent Coast. One always works the 11.38pm freight from Horsham to Battersea Yard via Leatherhead, a very hard duty; and on the Oxted line passenger services they can cope excellently with any shortage of tank power and also help to maintain a successful Lingfield race train program.

They give very little trouble in the shed for repairs, their only defect being a tendency to get rough in the coupled boxes and to get flats on the coupled wheels when working freight trains, after which they bump heavily until the flats have worked themselves out. On passenger work, the secret of keeping time with ‘N’ class Moguls is to work them hard up the bank and then let them find their own speed downhill. Seventy mph is plenty fast enough for one of these engines, but the heavier they are worked uphill the better they like it and the boiler will find all the steam necessary.

I remember one summer's day riding on No 31811 from Whitstable to Victoria; we were running late but surprisingly enough got a clear road through Chatham and over Rochester Bridge Junction. When we were past the end of the viaduct, we had all signals off, and so we decided to regain some of the lost time. This engine was riding rather roughly, so for a start it was essential to regain some of the time up the 1 in 100 of Sole Street bank. With full regulator the lever was set on ‘4 bars’, which, 1 suppose, would be about 45 per cent cut-off. One injector was on continuously and the fire was kept right up under the fire-hole door and half-way above the level of the bottom of the mouthpiece, so that the sliding doors would be kept open and coal requiring to be put on shot over the top of that at the back of the firebox. This method restricts the cold air entering the firebox via the fire-hole door and also prevents the coal from being drawn forward by the blast to the front of the box. The engine steamed very freely and, as we hoped, time was gained up the bank. Once over the top, the lever was brought back to about ‘3 bars’, and the first valve of the regulator only used downhill. We must have reached 70 through Farningham Road, where the engine gave us a rough ride; then a touch of the second valve up Swanley bank kept the speed well up around the 50 mark.

But the reliability of the ‘N’ class cannot be surpassed by the soundness of the old Wainwright ‘C’ class 0-6-0’s. A ‘C’ can always be guaranteed to get a heavy un-banked train of empties from Stewarts Lane to Victoria up the Lambeth Yard bank and on to Grosvenor Road bridge without coming to a stand. Perhaps the ‘C’ class engines are at their best on the freight job worked by Stewarts Lane from Hither Green to Hoo Junction via the Dartford Loop. The rockets fly on this job, and how these little engines steam! The footplate is an ideal one and the engine can be fired sitting down with small shovelfuls - little and often. It was always my regret that their day on the Ramsgate excursions had passed. I should liked to have gone to Ramsgate with one, for they used to take eight, nine or even ten bogies down this road hard work but good training for anyone who wanted to master the art of firing an engine.

For those firemen who wanted to broaden their minds, the LNER ‘Bl’ class 4-6-0s that were loaned for a time to the Southern Region provided further experience. When these engines arrived in 1953, they were fresh to everybody at the depot except myself. As far as steaming and running were concerned, they were well liked, but most of them were very rough - nevertheless they did well!

I was surprised, too, how the ‘B1s’ liked the soft Kent coal. I rode on No. 61192 from Faversham to Victoria one evening, and she steamed splendidly up Sole Street bank on Kent dust with a load of eleven bogies. I am afraid that we ran one or two of the ‘B1’s hot, but apart from that they did well and made a change at the shed. For all that, I was glad when they went home because, as the only person who really knew them, I was kept pretty busy in looking after them, and also in loyally defending them from time to time for the sake of old LNER!

This article would not be complete without mention of two more classes of engines, both famous in their own spheres; the Brighton Atlantics and the two Stewarts Lane ‘Britannia’s – No’s 70004 ‘William Shakespeare’ and 70014 ‘Iron Duke’. No Atlantics are stationed in London now but our men occasionally worked them on the 6.10pm Victoria to Uckfield. They are wonderful locomotives. Once up Grosvenor Road bank, it was child’s play to work ten bogies to East Croydon in 17 minutes. Like the Great Northern Atlantics, these old engines would run. Their roll and beat and whole motion was the same. As on most Brighton engines, the steam pressure gauge was up in the fireman’s corner, away from the driver’s compelling eye; unlike most Brighton engines, the Atlantics would steam and consequently the gauge could have been put in the normal place, above the firebox, as on the engines of other lines. The Newhaven men always were the experts with those engines, and still remain so.

R. H. N. HARDY – SHEDMASTER (73A)