CHRONICLES FROM EXMOUTH JUNCTIONINTRODUCTION - WEST OF ENGLAND Whilst we occasionally relieved each other at Salisbury on the West of England service trains few real friendships were ever forged with crews either from Salisbury, Yeovil or Exmouth Junction depots. Usual information concerning the locomotive’s condition were imparted in the brief time available during the station change-over duties when certainly water and coal were the principal focus of both the firemen concerned. The relieving fireman would attempt to get some coal forward in this time, whilst the relieved fireman swung the water column round and, once up on the tender, held the pipe in position whilst hundreds of gallons of water entered the tender tank below. The relieving driver on the other-hand was responsible for controlling the water filling the tender to its maximum. Whilst this was happening the relieved driver went and checked the valve-gear, feeling the bearings for any sign of over-heating and equally providing some additional lubrication during this inspection.

Fortunately however I did get to know a few of my counterparts, one in particular became a good friend of mine, namely Ted ‘Smokey’ Crawforth from Exmouth Junction (72A). As such, and on his behalf, I am more than pleased to reproduce some of his vivid memories that he recorded during his time at the Southern’s Exeter depot that I’m sure you will enjoy reading. In the first of a series of memoirs you will join Ted both in the depot, on the ‘local’ branch lines with ‘Push and Pull’ services, on a ‘Meldon Quarry’ stone train working to Salisbury and later with trips over the ‘Withered Arm’. So make yourself a nice cup of tea, turn the clock back and imagine that you are back in the late 1950’s and enjoy these descriptive railway events as they happen. Jim Lester – 70A

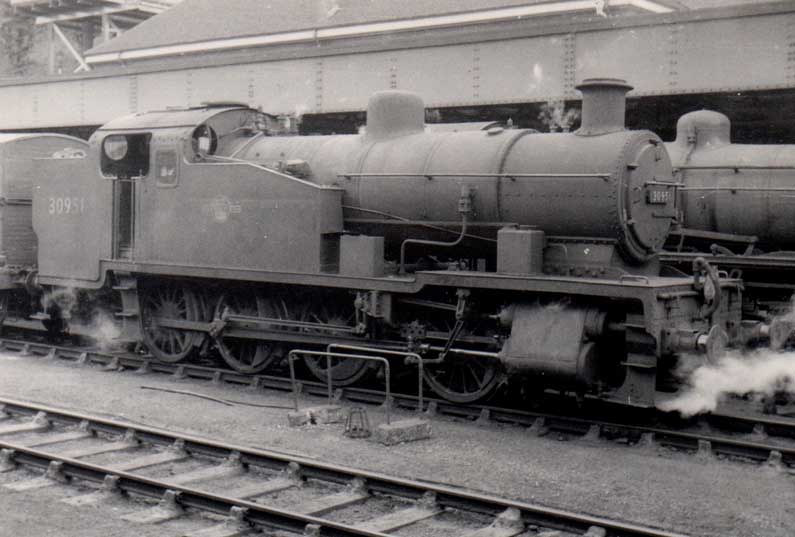

CHRONICLES FROM EXMOUTH JUNCTIONPUSH & PULL WORKING In continuing our look at the work being done by the ‘Junior Spare Link’ at Exmouth Junction depot in 1960, we come to the push - pull trains that ran on the Seaton branch. For those readers not in the know a push - pull train consists of a small tank locomotive and up to four coaches specially fitted so that the locomotive can propel the train with the driver located in a driving compartment at the leading end. He has there a remote control for the regulator, a brake valve, an air operated whistle and a bell for communication with his fireman, who remains on the footplate. The locomotives that we used were Drummond 0-4-4T ‘M7’ tanks, fitted with a Westinghouse pump for the air operated regulator control. In the cab was an air cylinder/piston linked to the regulator handle. When the train ran engine first the driver disconnected the cylinder linkage by withdrawing a pin and driving the engine normally. When running train first the fireman was on his own on the footplate with everything else to look after, and if anything went wrong with the actual control gear he would have to be prepared to take command of the engine as well. Due to the nature of this work, push and pull work was not rostered to junior firemen but to the ‘Junior Spare Link’ whose men would have done some ten years on the railway. A fireman had to pass through a training course to ensure that he fully understood not only the management of the boiler but also the operation of the reversing gear, brakes, lubricators and sanding gear, subsequently a register was kept of all the firemen who were qualified to work push - pull trains. When the driver was in the far driving compartment he signalled his intention to start the train and waited for the fireman’s acknowledgement. The fireman was responsible for making sure that the handbrake was off and the reversing gear correctly set before he gave the acknowledgement signal. While running he always had the option of stopping the train by applying the automatic brake, but otherwise he would inform the driver of any faults or problems at the first stop. He was expected to keep the normal lookout and was responsible for notching up the valve-gear over which the driver had no control. You would assume that the reversing lever would, when in the control of the man who had to produce the steam, be placed in a higher notch than it might be by the driver! On some designated lines, of which the Seaton branch was one, they could in certain circumstances be operated without a guard. As such his duties were then devolved to both the driver and fireman, these included such issues that concerned the coach lighting, passenger communication, closing doors, loading parcels and of course protection of the train in the event of a breakdown. At stations with staff on duty the station master or an authorised person was responsible for carrying out the brake test and ensuring the train was safe to start, whilst at halts the fireman closed the doors and gave the starting signal if the engine was propelling. At halts without proper platforms some push - pull trains were equipped with steps that were the responsibility of the fireman if there was no guard in attendance. The standard bell code between the driver and the fireman was as follows:

About to ‘open’ or ‘close’ regulator from driving compartment: 1 short The Seaton branch ran from Seaton Junction, which was located in open countryside near the hamlet of Shute, followed the course of the Umbourne Brook down through Colyton and Colyford to Seaton. It was 4 miles 16 chains in length and the running time was 10 minutes down and 13 minutes up. At the time that I was there, there were fifteen passenger trains each way weekdays, eighteen on Saturdays and eleven on Sundays. Nearly all were worked by a push - pull set, but there were ‘through’ coaches from Waterloo. On weekdays a coach was taken on the 10.02am from Seaton up to the junction and attached to the 10.17am or 10.30am from Exeter, whilst the 1.00pm from Waterloo left a coach to be taken by the 4.47pm down to Seaton. On summer Saturdays there were two through trains with ordinary coaches as well. Goods traffic was dealt with by a trip each weekday morning and a ‘mixed’ working when required. The branch engine, duty no. 606, started work with the up 7.50am service (6.32am on summer Saturdays) and finished at 10.08pm whereupon it spent the night in the small shed a Seaton, while the crew lodged in a hut between the station and the seashore. The hut itself was equipped with the usual bunks, sink, water tap, coal stove. There were two regular drivers on the branch and I remember them being as different as chalk and cheese! One was an easy going chap, but the other thought he was the ‘Lord Mayor of Seaton’ and would never so much as make a can of tea! My first Seaton turn was on the 20th August 1960, a Saturday, which was engine changeover day, the same as on the Lyme Regis branch. I booked on at 10.22am and travelled up passenger on the 10.37am from Exeter, and then I worked the 11.40am Seaton Junction to Seaton, which comprised through coaches off of the 8.22am from Waterloo. After five round trips on the branch (43 miles) we brought the engine, ‘M7’ No. 30045, back down to Exmouth Junction shed. The next turn was three-day stint during the week. On the Monday morning I booked on at 9.30am in the company of another fireman who was going to Lyme Regis, we later did the sands on eight engines in the shed. Later in the evening I caught the 7.50pm up (which was a through train from Plymouth to Eastleigh) and lodged the night at Seaton. The early turn started at 6.00am with the task of preparing the engine and coaling up at the coal-stage. First you filled the footplate up and used that to make up the fire, and then you filled the bunker up! There was a break from 10.53am to 11.41am at Seaton when we could come off of the train, do some shunted if needed, carry out some engine requirements and have a bite to eat! The turn finished at 2.15pm and the late turn crew started at 2.30pm. The next two days I spent on the late turn and our engine was No. 30125 - coupled to train-set No. 381. Then on the Friday I had to report back to Exmouth Junction at 9.00am to attend ……. the push - pull course!

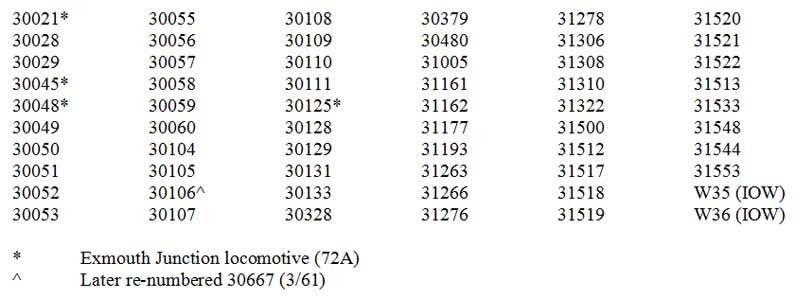

To close this section here is a list of Southern locomotives fitted for push - pull working, Drummond ‘M7’, Wainwright ‘H’ and Adams ‘O2’ 0-4-4T tanks. (List dated - 05 April 1960).

One of the colourful characters that we used to meet about the railway in those days was a relief-shunter whom they used to call Garth! Built like a barn door, with great muscular arms and a big bushy moustache he was somewhat like an Air Force Wing Commander! He was immune to the weather, and even in the severest of winter conditions would be seen about the yards in his waistcoat. One day we were on 589 duty working the 3.30am Bude goods as far Okehampton, spending from 4.30am to 6.00am shunting at Yeoford where we found him at work in the yard! It was raining particularly hard that morning as we shunted up and down. Both the head-shunter and points man were well rain-coated but not Garth, he had his uniform hat on, no coat just a white nylon shirt! Along the track the lengthman trudged in, with his macintosh buttoned right up, hat pulled down and his hammer slung over his shoulder! As usual Garth greeted him with a cheery ‘How are you, alright’? ‘Yes not too bad’ dolefully replied the lengthman with a vast lack of enthusiasm, adding ‘old weather’s a bit rough’! Garth after considering the point for a moment agreed! ‘Anyway Garth when are you next up Exeter again’ continued the conversation? ‘Oh sometime next week or so, why’? Garth replied. ‘Well do you think you could get me one of those waterproof shirts while you’re up there’? A character of a different sort, well known to footplatemen, was the woman who ran the post office at Braunton. We didn’t have many complaints from the pulic about noise and smoke. I suppose that it was one of the hazards of life they accepted in those days, but this old tartar was always taking engine numbers as they stood at Braunton preparing to start away up the steep gradient to Mortehoe and Woolacombe. So I was especially careful when running in there to have the fire-door open, no black smoke or blowing off! She didn’t get my name or number in spite of my reputation! When working on the railways in the West Country you needed to be not only waterproof but fireproof as well! One morning we were going down from Yeoford towards Barnstaple with a goods train and it started to rain and clouded over really dark. We came around the curve at King’s Nympton, my mate was bringing the train speed under control for the tablet change when there was a terrific lightning flash and a clap of thunder! Moments later, as we approached the platform, I was amazed to see another brilliant flash, this time from inside the signal-box! Suddenly the signalman, tablet in hand, came reeling down the box steps and across the platform spinning like a top! I called out to my mate ‘Whoa! We had better stop and help him’, so we stopped and ran back to the individual and sat him down on a platform seat. He said that he’d passed on the bell code and received permission to get the tablet for us, then just as he took the tablet from the machine there was a flash and everything blew up in front of him. When we up into the box we saw that it must have been struck, there were dials with twisted needles, instrument cases with ‘gubbins’ blown out of them and burnt wires everywhere! The telephones and telegraph equipment were gone but as we already had the tablet for the next section we put the one we had brought in from Eggesford beside the bemused signalman then proceeded on to Portsmouth Arms. We then alerted the signalman to get help out to King’s Nympton where things eventually were put back in order! That autumn of 1960 saw the west of England hit by the worst flooding seen for sixty years. On the morning of the 30th September the waters pouring off Dartmoor overwhelmed the railway, covering track and washing away ballast. The Yeoford signalman watched a three-feet deep torrent of water replace the main line outside of his box, whilst east of Crediton the river Troney took out a mile and half of track and swept away bridge No. 547, this then isolated the Southern Region from Crediton downwards, with some thirty engines marooned in various places with their trains! In order to get around the blockage you had to go either down the Western line to Plymouth and back or go up to Taunton and down to Barnstaple. To keep the traffic moving special train services were arranged, both passenger and goods, with Crediton – damaged by flooding – acting as the terminus for local services. On the 1st October I booked on at 2.15am for a goods working from Exmouth to Plymouth that ran via the Western. We left the yard tender first and ran around the train at St. Davids. Our engine was ‘West Country Class’ No. 34023 ‘Blackmoor Vale’, the load was thirty plus wagons and the only other thing I do remember about the trip is that we left the banking engine behind going up Hemerdon bank. Meanwhile back on the main line in the early hours of the morning the 1.15am newspaper train ran in to a slip on Honiton bank. It was later found that there were no less than 30 slips the whole length of the bank! The line was actually cleared and reopened in time for the passing of the newspaper train on the morning of the 3rd October, but the services were disrupted for sometime. The 1.45pm from Axminster reached Exeter at 5.10pm, the train from Brighton finally arrived double-headed by 82019 and ‘WC’ No. 34023, and an up special of 14 coaches were sent off with ‘WC’ No. 34039 ‘Boscastle’ and ‘S15’ No. 30844. Two more ‘S15’s No’s 30842 & 30845 were sent to Seaton Junction for banking purposes! Then if that wasn’t enough a bridge collapsed at Exton on the Exmouth branch and two more threatened by the floods. The 5.45pm fast to Exmouth was re-routed via Sidmouth Junction, while bus services were put on between Topsham and Exmouth. The following three days I was due to work some Exmouth turns so I went down on the bus only to find Exmouth inundated and boats out in the streets, as such we worked between there and Tipton. By the 6th October bridge No. 547 had been partially rebuilt but then more heavy rain came down demolishing it and washing away materials and equipment! Eventually the civil engineers had completed the work and had it opened by October. Still on the subject of water, during the freeze-up of 1962, I can recall there were reports about dangerous icicles that were precariously hanging in a tunnel mouth stopping trains entering! As such on one occasion the framework of the front canopy on our ‘BB’ class engine, No. 34079 ‘141 Squadron’, smashed into the stalactites that had formed during the Christmas holiday. Come Boxing Day at nine o’clock in the morning the first down train passes Tavistock North and pushes on down the Tavy valley. She comes to a short tunnel but no sooner had she poked her nose inside than my mate shouts across the footplate ‘Icicles, down’! Clang! Stopping at Bere Alston, I went round to the front of the engine and found them lying by the smoke-box door, several feet long and as thick as a man’s arm! A ‘Junior Spare Link’ job that I have already mentioned was Broad Clyst and Newcourt goods. Having been to Broad Clyst and shunted out the wagons there we would come back into Exmouth Junction yard where we would shunt there a bit to assist the yard pilot before going off to Newcourt. When we arrived in the yard, first things first, fireman goes off to make the tea! One day I bowled in there, the usual chat was going on, and there right behind the door sat the ‘Right Honourable Mayor of Exeter’! This exalted personage was in fact a yard foreman there, his place being taken by the head-shunter for a year whilst he was away doing his civic duties in the city. Holding such a position is a great honour and I didn’t know whether to stand up or sit down, take my hat off, salute or anything else? However he just waved me to carry on towards the kettle, it was while I was pouring away that I gathered from the conversation that he was feeling a bit railway sick (a once common condition among railwaymen, rather like home sickness), so he had left his regalia behind and had sneaked down to the yard for an hour to have a cuppa and chin-wag with the boys! When old ‘Titch’ the points-man came in a few minutes later his face showed me exactly how I must have looked on finding such a distinguished visitor in the cabin!

CHRONICLES FROM EXMOUTH JUNCTIONA TRIP ON A MELDON STONE TRAIN Because the general public does not, on the Southern railway that is, usually travel by goods train, the enthusiasts and the press tend not to give little attention to what has been the much more important part of railway business. Southwest England, although the birthplace of the world’s mining industry, is not associated with heavy freight or mineral haulage but when I was firing at Exmouth Junction we handled a fair amount of traffic, mostly general goods moving in and out of the region. Among our regular jobs were the express services such as the ‘Tavy Goods’, which we worked between Exeter and Salisbury, equally we worked the ballast trains from Meldon quarry! The LSWR first began extracting granite from Meldon in 1897, since when it has supplied several hundred thousands of tons for the whole of the Southern system. The resulting hole in the ground is huge and will probably remain to puzzle many future generations. The quarry lies on the edge of Dartmoor, near the 950 ft summit of the Southern’s mainline to Plymouth, and is crossed by the Meldon viaduct, whose steel lattice towers can be seen from the road two miles west of Okehampton. The ballast was carried in vacuum brake fitted 40-ton capacity hopper wagons, and a typical load would be ten of these and a brake van, grossing about 600 tons. From Meldon to Exeter the road is all downhill (similar to the much better publicised descents from Shap and Beattock) except for two short stretches at North Tawton and Bow. As such a 2-6-0 Class ‘N’ was quite able to handle a train down to Cowley Bridge Junction where we always got stopped before being allowed to venture onto the Western! Sometimes a Class ‘WC/BB’ might be used, or on one occasion we worked ten loaded hoppers down with an LMR Ivatt Class 2MT 2-6-2T. As we virtually coasted over the twenty-five miles or so there was naturally a tendency to try and see just how far you could run without applying steam and as a consequence speed would vary from a walking pace to 60 mph! Indeed I remember one day with a Class ‘N’ and ten loaded hoppers one of our younger guards got out of his van as we came up to the summit at Bow and pretended to push behind!

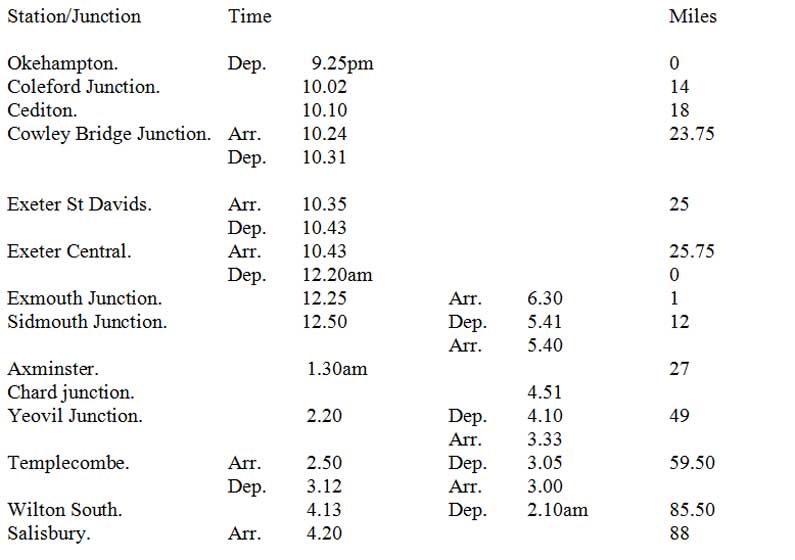

While these movements were in progress Okehampton would phone Exeter to advise them of the weight of the train and of the motive power on the front so that the correct banking engines were available. That little LMR tank would have required three bankers, one on the front and two on the rear, but on most occasions with an ‘N’ or a ‘WC/BB’ they had two on behind. The class of locomotives used for banking could vary from ‘Z’ 0-8-0T, ‘700’ 0-6-0 or another ‘N’ or ‘WC/BB’ or indeed whatever engines were available to do the shoving. I believed that these trains were generally over-powered rather then under-powered due to the fact that there were several set of ‘catch-points’ on the bank and we couldn’t undergo the humiliation of having the stone train stuck and then trying to get that little lot on the move again on a sharply curved, 1 in 37 gradient. There weren’t many sound recordists about in those days but there were cameras that captured the event that certainly was a sight to see, pounding up that formidable bank amid all the smoke, steam and the glory! The booked timings for the 09.25 pm Okehampton to Woking stone train, which we worked to Templecombe, and the return empties from Wilton South to Exmouth Junction were as follows:

Now imagine yourself transported back in time and space to Exmouth Junction Motive Power Depot. Today is Friday the 9th March 1962, it’s 10.30pm at night and we’re about to sign on duty. Driver Frank Churchill and his fireman ‘Smokey’ Crawforth. Engine No. 30846 - Class ‘S15’ - 4-6-0. After signing on and reading the notices I go out and join the engine where she is standing in the dim lights of the yard floodlights, waiting for me to climb up onto the footplate. After tripping over some lumps of coal left by the fire-lighter I hang my bag on the cab side hook, actually there are boxes on the tender for your gear but they are always messy with oil and coal dust. Dig out the duck lamp from the box immediately under the seat, check for paraffin and light it up and survey the situation. First thing to check whenever you board a steam locomotive is of course the water level in the boiler. Tonight we have a full glass, plus 60 lbs showing on the pressure gauge and the fire is up under the door. There is a fair amount of soot on the boiler back-head, not quite like modern days where the locomotives are kept in beautiful condition by numerous people, remember this is 1962! Equally these old ‘S15’ goods engines rarely ever get cleaned these days! Not to worry, I crack the blower off of the face to clear the smoke then collect the ‘engine’ oil and ‘cylinder’ oil bottles and paraffin can and go off to the stores for the necessary lubricants and lamp oil. Returning to engine I fill the feeder for the driver and stand it on the tray above the fire-hole door and place the oil bottles by the boiler back to warm up. Now to fill the hydrostatic lubricator, check first that the steam supply valve has been turned ‘OFF’, then using a ¾” spanner remove the filler plug and tap open the drain plug and let the excess water out. Securely close the drain plug then, with the same spanner, and proceed to fill it with ‘cylinder’ oil. Once full replace the plug and tighten with the spanner then turn the lubricator ‘ON’. This requires the dedicated steam valve to be opened that then feeds steam into a condenser, subsequently the condensed steam, water, pressurises the lubricator when the lubricator’s water valve is opened. The lubricator is now ready for use once we begin to move! I must now check the rest of the tools; Head-lamps (4), Gauge-glass lamp, Shovel, Bucket, Hand-brush, Thick-pot, Coal-pick, Hand-hammer, Fire-irons (Dart, Pricker, Clinker-shovel), Discs (3), Detonators (12), Red Flags (2), Spanners, Spare Gauge-glasses and washers and finally a Storm-sheet. With all four lamps cleaned, filled, trimmed and lit I alight from the footplate, also taking with me the hand-brush and the ¾” spanner. The brush to both sweep clean the side running plates and the front of the smoke-box clear any char previously left there and the spanner, on an ‘S15’, to tighten the nuts of the smoke-box door lugs thus ensuring an air-tight closure! Two white lamps are placed on the tender lamp brackets to show the head-code for going down to the Central and I always take the other one with a red shade and put it on the middle buffer-beam bracket on the engine as a tail lamp. The drill is that when you get to the Central you can take the two lamps off, then put one of them on the footplate, take the other one round the front and put it on the smoke-box, then turn the ‘red’ tail lamp to ‘white’. Then if anything should happen en-route and you have to urgently go around to the front of the engine you know where you can immediately put your hand on the lamp with a ‘red’ shade in it! Being properly organised in this way means reducing any hesitation and delay that can sometimes avoid serious accidents. While I’m out there sweeping off the front I also look at the sandboxes, we’re in luck tonight someone on ‘Tools & Sands’ has already filled them! By now Frank has arrived at the engine and I tell him the oil is ready. Frank a quiet type of chap but he’s quite cheerful as he puts his bag on the driving seat, he looks around at what he’s got to work with tonight, and then begins his examination and oiling. While he does that I go to work on the fire. Open the back damper a shade and then push down what fire there is which may cover about three-quarters of the grate. We need some good lumps of coal as foundation to build on so I climb up on to the tender and bring some forward, then start to make up the fire! How much? Well as much as it needs really, experience of doing the job virtually every day in all conditions teaches you the correct amount. Now we are ready to move, initially back to the column for water. I then test the sands and both injectors, leaving the firemen’s side working to top up the boiler. The pet-pipe works off it so I can wash down the cab and boiler front and damp the coal. When the tender is full – but not overflowing – I make sure that the lid is closed and check that the coal is safely trimmed. Back on the footplate I isolate both water gauge-glass columns and drain them down releasing any pressure still in the glass. Then I remove and clean the gauge glass protectors in a bucket of hot soapy water in which I also wash my hands at the same time. After replacing the clean protectors I now reverse the process of isolation lastly ensuring that both gauges are functioning correctly. Then the final job – you’ve guessed it – make the tea!

It is now about 11.55pm and we are due off the shed, but before leaving the shed the hydrostatic lubricator is set to work. Firstly by opening the oil valve then setting the sight feeds controls that then allows small globules of oil to be carried forward to lubricate the valves and cylinders, one every 15 - 20 seconds. We look out checking both sides of the engine, touch the whistle and creep on down the yard and pause at the points-man’s hut. The clock in his office will tell him that we are about so he usually looks out to see us moving down. The information ‘Light to the Central for the 12.20am Stone Train’ will be called down from the footplate. He will then phone the signalman and gives us the tip when the dummy comes ‘off’ and then we’re away tender first to Exeter Central. As we run down to the Central we see from the signal indication on the gantry that our train is in the Up Yard tonight. The guard, having looked around the train, is waiting at the front end ready to call us back on to it. While he is giving Frank the details of the train’s weight, speed, brake force, etc, I couple up, including connecting the vacuum pipes as this train is fully fitted! As soon as I call out ‘All together’ Frank will open the small jet (vacuum ejector) on the brake valve, he then ensures that twenty-one inches of vacuum eventually registers on the gauge. Meanwhile I change the lamps round, whilst taking the ones from the tender forward I leave one on the footplate, then at the front-end I change the ‘red’ shade in the lamp and set the Waterloo – Plymouth head-code, top and middle bottom. Then it’s back to the footplate where I find that the guard has scrounged a cup of tea! He then goes off back to his van to carryout the regulation brake while I start to pay attention to the fire in readiness for our departure. The need to have the fire right when about to work a heavy train should be clear if you look at the gradient profile of the route ahead and do some simple arithmetic! If you place a 600 tons train on a 1 in 100 gradient such as that between us at the Central and Exmouth Junction there is a force of 6 tons trying to pull us back down the grade, which is getting on for half the rated tractive effort (TE) of the engine, itself only a theoretical figure. After that first climb we can run down to Broad Clyst but after face a further thirteen miles, eleven of them uphill, at around 1 in 100 as far as Honiton summit. After the following steep descent comes another climb of twelve miles up the Axe valley to Hewish, thereafter the road is what books describe as undulating to Templecombe and beyond. I can be expecting to be firing at regular intervals as far as Yeovil Junction and perhaps further to Milborne Port, shovelling a couple of tons of coal. Frank will be driving using all his experience and feel the weight of the train behind, the cut-off will vary between, say, 35% and 50%, not that it matters no one can see the scale in the dark anyway. Now the signalman has got road right for us, so as soon as we get a green lamp from the guard in the van we are ready to go. Frank sets the engine at 65% and starts gently forward taking up the slack in the couplings, not all the wagons have screw-couplings. Once underway exchange signals with guard – make sure he’s coming too! Now we’re straight into the grade up the 1 in 100. With the fire door shut and the back damper open and with Frank’s three-quarters open regulator the fire will soon brighten up a treat on the section up to Exmouth Junction. At the moment I’m looking out in order to spot the double arm signal at St. James’ Park and, after passing through the tunnel, getting a wave from Exmouth Junction signalman. Frank now eases the regulator back and winds her up to around 35% cut-off as we run onto the down gradient whilst I put my injector on! The next signal to observe is the ‘distant’ for Pinhoe, once sighted I indicate to Frank that it’s ‘Off’. After passing Pinhoe signal-box I turn my injector off, Frank has now opened her up again, so I start firing! Two down the front of the box, two to the middle then two at the back, producing as much steam as is needed but not too much – that’s boiler control! Looking out again this time to catch Broad Clyst‘s signals, now we are into steady climbing past Canneford Gates level crossing and Whimple. Apart from the signal indications Frank and I don’t have much to say to each other, we are just getting on with our jobs! Most of the time just the raising of your hand gives Frank the information that the signal he is expecting me to see is ‘Off’, the vital signal to look for is of course the ‘distant’. At this time of night some of the signal-boxes will be shut out, whilst others will be operational, the next one that is open will be Sidmouth Junction. As we pass the empty station the box appears like a square of light in the darkness, just a silhouette in which the signalman seems to float by with a friendly wave to indicate that everything is all right and we’re doing fine. ‘Better than it was the other week’ comments Frank. On that occasion we had just reached Sidmouth Junction when a big lump of coal jammed in the tender front and I broke the shovel in getting it shifted. We fired the rest of the way to Templecombe using the remains of the shovel and a disc-board! Onwards from Sidmouth Junction we descend down a 1 in 100 gradient to Fenny Bridges over the River Otter and starting the climb towards Honiton (for those of you that like these details), where we go over four bridges in quick succession. Then more steady climbing, up past Honiton Town and into the ¾ mile long tunnel. About a quarter of the way through the gradient changes in our favour so as the train comes over the summit Frank eases the regulator back and finally closes it. The blower is applied to stop any blowbacks from the downdraft in the confined space of the tunnel. We can now have a sweep up and pour out a cup of tea while the train runs its natural course down the bank, down past Incline box where old Smudger Smith will probably be sat in his armchair waiting for us to go by. Coming out of the tunnel I look back to see if the guard is still with us, in accordance with Rule 126. The four ‘Catherine’ wheels at the backend show that he’s got his van brake screwed on thereby holding the train tight on the downhill stretch like all good guards should! We hope that he doesn’t end up in the situation they had a fortnight ago when there was some paraffin spilt on the brake van’s floor and during the run down the bank our guard managed to set the van on fire with sparks from the wheels. This was fortunately spotted by the signalman in Incline box. He then alerted Seaton Junction, who eventually stopped the train and put the fire out! The guard suggested it was the Indians shooting flaming arrows at him! As you come down to Seaton Junction looking for the ‘distant’ signal you will see it cross from one side of the engine to the other in the spectacle glass before you go underneath it! There’s the signal-box, and another signalman who floats by in the dark with a wave. We feel the guard release his brake as we run under the bridge in the station. On now, down through the bottom of the dip by Whitford village, running alongside the River Axe, which we shall cross seven times before reaching Chard Junction. The next signal to look for is right up in the air for it is the 40 feet high ‘distant’ signal for Axminster. Now Frank is picking them up on the regulator again, and by the time we get to Axminster it’s a good three-quarters open! The rest is over and I’m back again firing, putting a round into the firebox at regular intervals. There are two crossing gates on this section of the line, one at Wadbrook the other at Broom, but they are usually locked out. The next open box is Chard Junction. That one is located on Frank’s side, so he’ll get the friendly wave. Whenever possible I will walk across myself to double check the signals, have a look at the box we are passing and generally satisfy myself that everything is in order. Then back to the firing, for she’s still into them up the long bank to Hewish. Past Hewish Crossing, where I’m told there were sidings during the war, then over the top at milepost 133.1/4 where Frank eases her back as we go down through the tunnel towards Crewkerne. ‘Here how many cups of tea have you had’? ‘I’ve seen you have four, I’ve had five and the can’s still half full’! It turns out the regulator gland has been dripping into it keeping it topped up! On down through Crewkerne station, the guard starts to wind his brake on to keep the couplings stretched out, till we get to Hardington Bottom, another location where there were sidings during the war. Here we pass over what we called the ‘Silent Mile’, it was the first length of long-welded track on the Southern, (I believe that when they had finished with it and it was taken up, and was put somewhere on the Western Region). We feel the brake come off and we’re away again, up over the hill to Sutton Bingham where there is another signal-box on the fireman’s side round the corner Frank shuts off just after the box and we run down through Yeovil Junction, past Wyke Gates where they are also locked out at night, on as far Sherborne’s ‘distant’. In later years the box at Wyke Gates finished up in the crossing keepers back garden as a shed. Picking them up again past Sherborne’s ‘distant’ – this is one we can both see as it’s on a slight curve – up through Sherborne itself and on to a steep bank, a couple of miles at 1 in 80 gradient to Milborne Port, then we get over the top of the summit and drop down into Templecombe, nice and gently into the station trying to stop her just right for the water column, perfect! The stone train stands in Templecombe station in the dead of night, with the injector singing as we fill the boiler to keep her quiet and avoid disturbing the local inhabitants. We’re standing on the up main line as the next train, the 3.40am local goods from Yeovil, does not arrive until 4.10am. By the time we have taken water and washed up the church clock, on the other side of the S&D line, is striking and we settle down to wait until the Salisbury blokes come in with our down empties. Once he’s about we walk down the platform, over the bridge, to change over with them and set off back home. The down timetable shows a long stop at Yeovil Junction, during which time the famous 1.10am paper train will have arrived, done it’s station business and gone off on its way. If we were running late there was no need to stop there, but if we got caught up by the 5.32am Yeovil Junction to Exeter parcels we would sometimes have to stop at Sidmouth Junction and shove back inside to let it pass, more often than not though by 6.30am I would be well on my way home! So that was the workings of the Meldon stone train in 1962. Nostalgically, thinking about it now I’m reminded of that old church clock at Templecombe, where the Somerset & Dorset ran, of the trips that I had on the line and lastly my broad bean dibber! Why my dibber you ask? Because it’s the remains of the handle of that shovel that I broke one night all those years ago!

LOCOMOTIVE PREPARATION & DISPOSALLocomotive preparation is covered in my description of preparing an engine to work a Meldon stone train, however I would emphasise the importance of the initial approach aspects of the task. Walking around the locomotive making visual checks, then climbing onboard, giving the hand-brake a tug ensuring that it is fully applied and that the engine is secure (drain-cocks open, reverser in mid-gear, regulator closed), checking that there is enough water level in the boiler and lastly the condition of the fire. All the other duties of a fireman then follow these primary, basic safety checks on a steam locomotive. If the engine is due out shortly you made up the fire, if not you would leave the fire and the driver would leave the trimmings out in the oil boxes then, when another crew came on later, who are booked to prepare the locomotive, the driver would replace the trimming and the fireman would make up the fire, then take coal and water before they left the shed. Alternatively the foreman might just require it as a spare! When you dispose of an engine you joined it on the pit where you immediately got up onto the tender and put the pipe in, once in position the driver gently turned the water on. Then while he was examining the engine for any defects it’s back on the footplate where you make sure that the lubricator is shut off. Next lightly put the blower on, then picking up the hand-brush, firing-shovel and ¾” spanner you went around the front-end and cleaned out the smoke-box. After sweeping the front-end off it was back to the cab and get the dart, pricker and clinker shovel down off of the tender in readiness to clean the fire. First you cleaned half the fire-grate area at a time, some depots did the front and back halves but we always did side to side, (a time honoured LSW practice). On BR Standard class locomotives with their drop grates you pushed the good fire forward first, then dropped the remaining clinker under the door, then you pulled back the good fire on the closed grate, then dropped the front-half clinker deposit. While doing this it was also your job to examine the condition of the tube-plate, brick-arch, fire-bars and stays. The driver might sometimes lend a hand with the fire on occasions! Next, with an ash-pan rake, you went underneath the locomotive and made sure the ash-pan was clean. By about now the tender tank would be full so turn off the water valve and throw the pipe out. Now up to get some fresh coal, after trimming the coal you turned the engine (if required) and stabled it. Then start on the next one! Usually you would put an engine in the shed with a little fire left in, made right up under the door. It could then be safely left for the firelighter to keep an eye on, thus saving him from having to carry shovels full of hot burning coal and loads of wood and mess about lighting it up again! When engines had a long stay on shed then all the fire would be thrown out! Occasionally you might strike lucky on disposal and get a ‘soft number’ this meant that someone had already done the fire and all you had to do was the coaling and turning. Ted ‘Smokey’ Crawforth – 72A

|

|

Site sponsored/maintained by SVSFilm © 2016 ... Go to SVS Film Index Go to Nine Elms Main Index - "Light to Loco" |